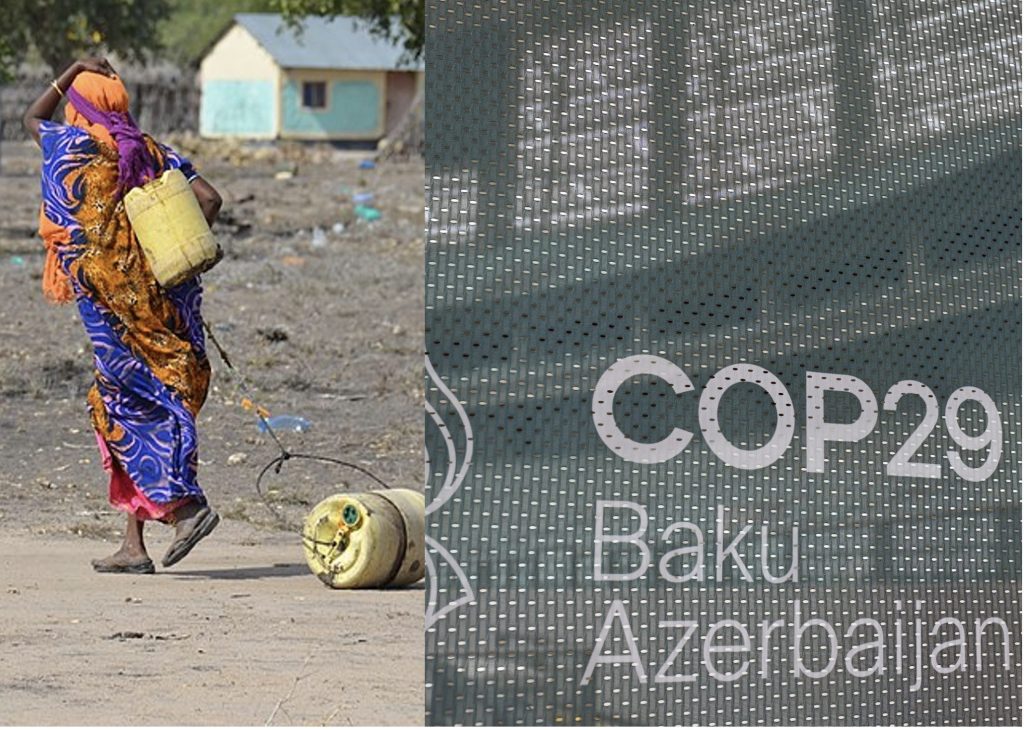

This year’s COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan will likely be a tamer affair than the last. With the number of delegate badges slashed, and businesses reportedly planning to either skip or send smaller delegations as a result of the US elections, accommodation challenges, fewer “business opportunities” and this year being more of a technical COP, it will likely be less of a jamboree than Dubai. The political tensions and pressure for a successful outcome, however, have not dissipated. Climate finance has always been a major issue on the agenda, but this year it will come out tops, with countries set to agree a new climate finance target for 2025 and beyond. The discussions around the new target will have cascading effects on finance for adaptation and loss and damage, as well as developing country appetite for more ambitious Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) which are due in February next year. In this article we highlight the key negotiation points at this year’s COP. While African negotiators will still be refining their draft Common Position on 7-8 November 2024, in a pre-COP plenary, we also trace some of their early thinking on the major COP negotiation points.

Finance

This year, countries are set to agree to a new finance target to fund climate action in developing countries, known as the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). It will replace the previous commitment made in 2009 for the provision of $100 billion/year by 2020. There are ongoing disputes about whether this has ever been met. Up until now 23 mostly high income countries, known as “Annex II” parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), have been jointly responsible for providing finance. But in the years leading to now, there has been increasing scrutiny, on the adequacy, nature, form, additionality and transparency of this finance. Knowledge of the volumes of finance needed has also increased. In September, the second UNFCCC Needs Determination Report found that US$5.012- 6.852 trillion was needed collectively in the period leading up to 2030 to enable developing countries to implement their NDCs. Moreover, global annual damages as a result of climate change are estimated to be at US$38 trillion, ranging between US$19-59 trillion by 2050.

This year, countries are looking to go beyond just a number and want to have a more detailed agreed framework around the provision of finance. However, with days to go until the beginning of the COP, they are still very far apart on several key issues. These include proposals to expand the list of donor countries, the structure of the target, and agreement on what counts as “climate finance”.

The African Group of Negotiators (AGN) have consistently pushed for an outcomes based target, and not one that is simply based on what developed countries are able to provide. In this sense the amount must be needs based and informed by the priorities of developing countries, in particular NDC and National Adaptation Plan implementation. In September, AMCEN publicly called for developing countries to commit to US$1.3 trillion annually, with the core of it being in public finance, with the majority in grant form accompanied by highly concessional loans. It should cover adaptation, mitigation and loss and damage, including finance for the just transition. It must be treated and reported on as finance provided by developed to developing countries under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement, which sets out the obligations of “developed countries” to provide finance, and must be informed by a clear definition of “climate finance”.

COP29 looks set to be contentious on almost all of these issues. To date, developed countries have been relatively silent on the amount of finance they are willing to provide, with discussions mostly diverging into how to incorporate the private sector. Developed countries also want to widen the contributor base. The United Kingdom said it “is ready to be a contributor, but a fit for purpose goal would need a broad range of contributors than is currently the case.” They cite changed circumstances since the conclusion of the UNFCCC, and a shift in major emitters and developing economy wealth. Canada and Switzerland, for example, proposed formulas for determining financial responsibility, which would result in the inclusion of Saudi Arabia, China, and Russia as contributors. But developing countries feel this is contrary to the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities under the UNFCCC, Article 9 of the Paris Agreement which is clear on developed country obligations, and the requirement for burden sharing between developed countries. Brazil also pointed out that while economies have changed, other institutions, like the IMF and World Bank which date back to 1945 had not changed to account for those realities.

Some countries, like France, Belgium, Ireland and Spain, believe that finance must go to the “most vulnerable” countries only, hearkening back to debates from last year under the loss and damage fund. The G77 and Gambia, as well as other developing countries, feel strongly that finance should go to just transitions and loss and damage as well within the NCQG. However, no developed countries has spoken of loss and damage finance yet.

Developed countries are also pushing for a “multilayer structure which attracts private finance”. This is contrary to the views of developing countries who want to see commitments that have a minimum public finance component.

Alongside these discussions will be debates around the reform of the global finance architecture. Almost 70% of climate finance between 2013 and 2018 was in the form of loans, which has exacerbated the debt burden of many African countries. For this reason, discussions will dwell on making sure finance is accessible, equitable, and responsive to the needs of developing countries and does not increase debt. Reforms within Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) will come up and the delivery of more concessional finance will also certainly feature. For more on this, and the continent’s need for equitable and accessible finance for its energy transition, see the analysis by Patrick Kwabena Stephenson in this week’s COP special issue.

NDCs

Countries are due to submit updated NDCs in February 2025, and many countries may be presenting their plans at the COP. The outcome of the NCQG will undoubtedly prompt the level of ambition in updated African NDCs, and the ability of the continent to meet any revised target. Under the Paris Agreement’s ratcheting mechanism these updated plans must represent a “progression” from the previous one and represent the country’s “highest possible ambition” whilst also taking common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities into account.

Countries will be hard pressed to find this highest possible ambition. The latest NDC Synthesis Report has found that existing climate plans fall drastically short of what is needed. When combined, current NDCs set the world on course for an emissions reduction of only 2.6% lower than 2019 levels by 2030. Compare this to the 43% that is needed by 2030, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Not only will countries be looking to see increasingly ambitious plans, but the NDC revision cycle is a moment to address the outcome of the Global Stocktake, including in relation to commitments to transition away from fossil fuels, triple renewable energy capacity, deliver on adaptation finance, and meet loss and damage finance needs.

Adaptation

One of the victories of COP28 was the establishment of a framework for the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). Countries were also encouraged to develop their National Adaptation Plans by 2025, and report on implementation progress by 2030. At COP29, countries will focus on how to track the implementation of the GGA, an issue Luckson Zvobgo discusses in his special feature on GGA indicators. At present countries are assessing the suitability of existing indicators to measure the GGA, for example, those used for the Sustainable Development Goals. But African countries feel that new specific indicators are necessary given the limited evidence of the suitability of existing indicators to track the GGA. And because indicators are such a technically led process, it is best left to technical experts (and not the existing Adaptation Committee), to drive this process. Ideally COP29 must establish a party led Ad-hoc Expert Group chaired by two people, respectively from developing and developed countries, as the current arrangement is felt to be untransparent. Undoubtedly African countries will want to see indicators to track means of implementation (especially finance) of the GGA, something that developed countries have also been pushing back against. Given the preliminary nature of this work though, a final outcome on the indicators is only expected next year.

COP29 will also be expected to deliver additional guidance and recommendations on how countries can prepare and implement their NAPs. This will follow an assessment of how NAP implementation has fared since 2018 focusing on what has worked and what has not. Key to the success all of this will be for negotiators to ensure that adaptation is adequately financed and supported under the NCQG.

Article 6 and Carbon Markets

Article 6 applies to market and non-market mechanisms, and enables countries to trade carbon offsets (ITMOS) between them to achieve their NDC and other targets, and also creates a successor to the Clean Development Mechanism, known as the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM).

The COP29 Lead Negotiator for Azerbaijan identified Article 6 as a major priority for this year’s discussions, noting that it is “the second major expected deliverable of COP 29”. His statement predicted that the current financial value of these markets, currently pegged at around US$2.2 to 2.5 billion, could be increased “multiple times”. But growth must also address global concerns of greenwashing and the integrity of carbon credits.

To this end, at COP29 countries will be seeking to finalise the rules for carbon markets, to ensure that they are transparent and deliver on environmental integrity, additionality and do not lead to the double counting of emissions. For African countries, the priority will be to negotiate rules and systems that promote transparency across different reporting requirements, but also reduce administrative burdens. The group is also looking to see the establishment of a functional international registry for carbon credits (under Article 6.2), and a clear and logical sequencing process for their transfer.

At present only the transfer of PACM credits triggers the need for a financial contribution (called a “share of proceeds” amounting to 5% of issued carbon units, and 3% of the issuance fee) that must be transferred to the Adaptation Fund. Historically under the CDM, this amount led to a steady source of finance being accrued for the Adaptation Fund, which has been plagued by a lack of resources. African countries are looking to ensure a similar mechanism is introduced for the trade of ITMOS (country to country transfers of credits under Article 6.2). At present countries can voluntarily transfer a share of proceeds to the Adaptation Fund. If parties were to commit to transferring a share of proceeds for Article 6.2. transfers of ITMOS, this would then boost sources of reliable adaptation finance.

For a deeper discussion on the decisions that need to be taken on Article 6, and Africa’s positions on the market, see the analysis by Clarice Wambua in this week’s COP special edition.

Just Transition and Mitigation

At COP27 countries agreed to establish a Just Transition Work Programme, as a forum to discuss pathways to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement. Last year, countries defined and agreed to the programme’s objectives in broad strokes. But questions remain about how to further refine and implement it. The G77 and African countries are asking for a detailed workplan that ensures a more structured dialogue focused on implementation. But some developed countries have argued that a work plan is premature, wanting rather more time to build consensus on the overarching goals of the programme, and to assess capacity before committing to specific steps for implementation. This has led to the forum being critiqued as a “talk shop” lacking specific steps for implementation.

This comes down to countries disagreeing on the real objective of the forum. Is it about protecting employment and jobs (developed country view) or does it have a more expansive reach to include social justice, environmental sustainability and economic transformation (developing country view)? As a result, earlier this year, countries also could not agree on how to involve stakeholders through social dialogue or on how to cooperate internationally. At the COP African countries will want to see consensus around the real scope of the programme and a structured approach adopted through a detailed work plan geared for implementation.

For African countries, another key issue is ensuring that unilateral measures taken in one country (for example the CBAM) do not increase inequalities in other countries. Moreover, national priorities and circumstances should take precedence when determining what a just transition is, and should not be dictated, by the terms of just transition finance. For example financial instruments that deepen the indebtedness of borrow countries to facilitate a just transition, should be discouraged.

Running parallel to the Just Transition Work Programme is the Mitigation Work Programme (MWP), which has been witness to similar disputes about its real mandate. Earlier this year, countries clashed on whether the MWP is a vehicle for target setting or not. This has been a historic issue with developed countries in the past seeking to encourage sector driven targets in this forum. Developed countries are looking for “strong outcomes” from the MWP and want to discuss targets or common mitigation measures in the programme. Developing countries however feel that the MWP should rather be for a focused exchange of views and ideas. The issue came to a head when countries disagreed whether the MWP should be the programme through which the recommendations of last year’s Global Stocktake should be implemented, and whether it is the forum to engage on the future content of NDCs. A particularly contentious issue is whether the MWP should be the forum for determining how to implement paragraph 28 of the Global Stocktake outcome document which relates to the “transitioning away” from fossil fuels. There is a feeling amongst developing countries that developed countries are seeking to revisit a mandate that was agreed to last year. It is also felt that developed countries need to take the lead on mitigation. Brazil, for instance, raised concerns about a rumour that they have been trying to bury reports that project that Annex 1 Parties’ (developed country) emissions will increase in 2030 compared to 2020. But when it came to finance, “for developing countries, they block conversations and go back on decisions agreed to even in the recent past.”

At COP29, African countries are looking to rebuild trust in this space, and to reframe the mandate from one of negotiation to one of implementation. This hearkens back to the desire for the Just Transition Work Programme to also be implementation focused.

Trade

We have continuously written about the failure of the COP to provide a platform to discuss trade, and the challenges faced by African Countries in addressing this issue within the UNFCCC’s Forum on Response Measures and the Katowice Committee of Experts. This may well change. Recently the BASIC group of countries (Brazil, China, India, and South Africa) submitted a request to the COP29 Presidency and the UN Climate Change Secretariat to add the following item to the climate conference agenda: “Concerns with climate-change related unilateral restrictive trade measures, and identifying the ways to promote international cooperation in line with the First GST Outcome”. This would include measures like the CBAM and the EU’s deforestation regulations. It would be critical for this item to make the formal agenda at COP29 if countries are to have meaningful engagements on what are arguably the largest cross-border mitigation related measures taken by any country or group of countries to date.

Loss and Damage

Loss and damage is less of a feature this year than it was at COP28, following the agreement to establish the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (L&D Fund). Incremental progress was made this year, during which the Philippines was selected as the host for its board, working relationships were established with its interim host, the World Bank, and its Executive Director (ED) was appointed. Ibrahima Cheikh Diong previously the UN-Assistant Secretary General and Director General of the African Union specialised agency, the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group is the appointed ED.

This year’s COP anticipates the approval of these steps, including the Financial Intermediary Fund (FIF) documentation prepared by the World Bank. It will need to ensure that the terms upon which the World Bank hosts the fund comply with the conditionalities of independence and direct access that were stipulated last year.

This year, there will also be the added focus on delivering loss and damage finance, by ensuring it is part of the NCQG. Readers will recall that last year was a bitter disappointment on this end, with developed countries only encouraged and not obliged to provide finance to the new Fund.

Parties will also review the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM), a body tasked with ensuring better knowledge of risk management approaches, stakeholder dialogue and coordination and enhancing action and support for loss and damage. The purpose of the review is to strengthen its role and facilitate coordination with the L&D Fund, and the technical assistance arm for loss and damage, the Santiago Network.