COP negotiations have become something of an annual sport, requiring unprecedented levels of mental and physical stamina from its participants. Not only are the final days and nights long, the blue and green zones difficult to navigate, and the physical distances far to traverse, but understanding the agenda and the breadth and complexity of the issues under discussion can be daunting, even for seasoned negotiators. The scale and nuance of the issues under discussion has amplified and fragmented over the years, with negotiation teams often having dedicated negotiators assigned simply to cover a single issue. In an attempt to set the agenda and streamline the issues, COP Presidencies and key players have often sought to dub a theme for the COP and carefully structure the agenda around it. For instance some have called this year’s COP the “African COP”, the “Implementation COP”, the “Climate Finance COP”, or the “Adaptation COP”, and the Egyptian COP Presidency has been forthright on what it wishes to see prioritized at this year’s negotiations.

This may well be the case in respect of the agenda and its structure, however, as last year’s COP demonstrated, with the late surfacing of Loss and Damage debate, these themes are by no means determinative. The unformed agendas, political controversies and global events that have dominated this year’s multilateral meetings, and that tend to precede every COP, will undoubtedly influence how the negotiations proceed and will determine the “crunch issues”. These dynamics include the war in Ukraine, the global energy crises and associated concerns about a backsliding of ambition; discussions circling Africa’s use and export of transition fuels and heightened demand for LNG from the EU and elsewhere (including the general promotion by Egypt of LNG as a transition fuel); the increased intensity and severity of extreme climate events and associated loss and damage such as the flooding witnessed in Pakistan and Nigeria this year; the unprecedented levels of debt distress within African and other developing countries as they struggle to recover from the pandemic; the focus on other non-state actors such as the IMF and World Bank to play a changed and more meaningful role in the global climate response; and the ever growing levels of civil society unrest and litigation in response to inadequate national responses to climate change.

In this briefing note we grapple with what we believe are likely to be some of the key issues on the table, as made relevant to African participants and negotiators.

New Climate Finance Target

Climate Finance was a key issue at COP26 and will remain so this year. In 2009, developed countries pledged to provide US$100billion/year in climate finance to developing countries. Last year discussions commenced on a New Collective Quantified Goal for (NCQG) for climate finance which would supersede this commitment from 2025 onwards. Developing countries are also being pushed to take on more ambitious climate targets and move towards net zero, and are asking why they should do so if the necessary financial support is not forthcoming from developed countries. In this context, a lot of attention has been focused on extent to which developed countries have actually been able to deliver on their previous promises to provide climate finance. The OECD is de facto the most authoritative (albeit not globally agreed and by no means uncontested) source of tracking global flows of climate finance. In their latest report, they confirmed that US$83.3 billion had been provided in 2020, still leaving a shortfall of $16.7 billion. The shortfall it is both quantitatively and symbolically important to developing countries, mindful that the $100 billion target falls far short of what is actually needed.

For these reasons, developing countries are asking for developed countries to make up on the shortfall and for more progress to be achieved on agreeing a new target for the NCQG. Last week the Climate Finance delivery plan was released by Climate and Germany. It has been supported for providing a clearer pathway on the way forward but has been criticised for failing to require that developed countries make good on their historic shortfall by providing US$600 billion in finance between 2020 and 2025.

At this year’s COP African countries are looking for a new target of US$1.3 trillion per year by 2030, of which 50% is for mitigation and 50% is for adaptation with a floor of US$100 billion. Given that many countries are debt distressed, and that most climate finance is concessional and not always on favourable terms, African countries are also asking for finance that is primarily grant based, meaning that it is provided by the public sector and does not exacerbate debt. It remains to be seen how this will be received by developed countries, many of which are engulfed in their own energy crises, or which are facing fiscal constraints. Historically developed countries have deflected attention from their own obligations by stressing the importance of “reigning in” other sources of finance particularly from the private sector. For instance, the United States in the negotiations has tended to point to the need to incentivise and catalyse the private sector with the right enabling policy and regulatory environment. In doing so they have sought to argue that the definition of finance should be broadened to include a much wider array of actors (i.e., beyond those that would provide public grant or highly concessional funding). It is for this reason that the definition of what counts as “climate finance” is so controversial and is likely to be under discussion again at this year’s COP.

Adaptation Finance

Last year developed countries were “urged” under the Glasgow Pact to double the amount of adaptation finance they provided by 2025. This would be equivalent to about $40 billion. Going into this year’s COP, African countries are looking for developed countries not only to honour the pledges and commitments they made to replenish the Adaptation Fund, but also to have deeper discussions on how the doubled adaptation finance will be channelled. To help ensure this finance is accurately accounted for and more accessible, African countries are looking to have it channelled through the Adaptation Fund and for the issue to be put on as an agenda item to discuss the modalities of how this would work. Unsurprisingly there is also a desire to see more grant-based adaptation finance.

Similarly new sources of adaptation finance are being pursued and it is possible that African countries will argue to see a percentage share of global carbon credit transactions (through Article 6 of the Agreement) dedicated towards adaptation funding.

Loss and Damage

Loss and Damage took centre stage last year when the G77 plus China asked for a dedicated loss and damage finance facility. This finance is needed separately and in addition to mitigation and adaptation finance to respond to climate impacts that have already occurred. The proposal was rejected by developed countries and instead parties agreed to establish a two-year discussion called the Glasgow Dialogue on Loss and Damage. A session was held this year at the Bonn intersessionals but it was not formally incorporated into the work programme. To date, the EU and the G7 have supported the Global Shield (a form of disaster insurance) but there are early, albeit unclear, signs that they may also agree to a dedicated finance facility. The US is less supportive but has said it is open to talks. New Zealand, Scotland and Denmark have been the most supportive within the developed world. It will likely be a contentious issue again at COP27, with high civil society support for the topic, but given the US position and historic successes it has had in thwarting progress on this issue, the way forward is unclear.

Although it is supposed to be treated as the third pillar of the global climate regime next to mitigation and adaptation, loss and damage also tends to be treated as part of adaptation. Partly for this reason, Parties have also been fighting hard to have Loss and Damage established as a formal independent agenda item at the COP this year. So far, the Secretariat has only agreed to a proposal by the G77 plus China to include “financing options for loss and damage” as a sub agenda item. This will only be for COP27 (it is not a standing/annual agenda item) and it is also limited just to the narrower issue of finance. As such, it will be a win for developing countries if it can be agreed to as a standing agenda item. There does not appear to be much proposal from developed countries.

Countries also agreed last year to operationalize and fund the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage (a body that connects developing countries with providers of technical assistance, knowledge and resources). The network’s functions have been agreed on, but parties still need to agree on the institutional arrangements to deliver on the functions (where it is hosted, how it is structured, who oversees it and how it is funded). The debate is mostly about which body will oversee the network and whether a new one or existing one can do so.

Fossil Fuel Phase Outs, Just Transitions, and Subsidies

Last year the Glasgow Pact, in relatively non-committal but highly contentious language, underscored the need to accelerate efforts to “phase down unabated coal” and phase-out “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies.” In a separate pledge outside of the Paris Agreement, 46 countries, including the U.K., Canada, Poland and Vietnam agreed to “phase out” domestic coal. An additional 39 countries committed to end new overseas finance of fossil fuels by the end of 2022 and redirect this investment to clean energy.

Progress on domestic phase outs is important in the negotiations as it is unlikely that developing countries will budge on the issue of climate finance if developed countries don’t demonstrate commitment to their own domestic pledges. In July this year the IEA stated that coal burning was set to rise in 2022, taking it back to levels last seen in 2013. This year Germany, Austria, France and the Netherlands all announced plans to reactivate coal-fired power plants as a result of the energy crisis. This is likely to be in the short term only and it will be interesting to see how countries implement the REPowerEU plan going forward (which has a higher renewable energy target and reduces gas significantly). The US, which has the world’s third-largest number of coal plants, has not set a national end date for its coal power, unlike the UK, France and Italy. In relation to fossil fuel financing, whilst the G7 has affirmed its position to end to end direct public support for the international unabated fossil fuel energy sector by the end of 2022, exceptions have been made by the EU for finance for natural gas in the shorter term.

Whilst dealing with their own domestic crises, developed countries are seeking to sweeten the deal to decarbonise for emerging economies by offering financial support to phase out coal and support a Just Transition. For this reason, a lot of attention will be focused on the South African Just Transition Energy Partnership (JETP) example, and the offers made to Indonesia, Vietnam and India. Recent reports suggest that only 3% of the South African JETP is in grant form, and it is questionable if it is fit for purpose for South Africa. This may put off emerging economies agreeing to similar coal phase out deals.

At the negotiations, developing countries will likely be asking for clearer policies and support for Just Transitions and possibly a Just Transition finance framework. African countries will likely push to ensure that this finance is dedicated, equitable, and accessible and that it is also responsive to national circumstances, most notably that it does not exacerbate debt.

Mitigation Ambition

At Glasgow last year all Parties agreed that they would “revisit and strengthen” their NDC 2030 targets by 23 September 2022 with the aim of closing the gap to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees. In the months since, Russia’s war in Ukraine and rapid inflation have caused global energy and food prices to soar, raising a concern by the COP Presidency that there will be “backsliding” on commitments. In particular concerns have been raised following the last G20 meeting, that some countries including China are objecting to language that limits the global average temperature rise to 1.5oC, notwithstanding previous commitments in the Glasgow Climate Pact around this target. Apparently, China and India are in favour of language that supports a 2oC goal.

The latest NDC Synthesis Report by the UNFCCC found that even with revisions from this year and some modest improvements in emissions reductions by 2030, the combined level of effort in revised NDCs still puts the world on track for 2.5oC warming by the end of the century. It still found that emissions were due to increase by 10.6% by 2030 (instead of being cut by 45%). In positive news, Australia has significantly improved its previous pledge and has committed to reduce emissions by 43% by 2030, and domestic action within the US puts it on a path to achieve a 50% reduction by 2030. Indonesia, India and Egypt have also submitted more ambitious plans.

In Glasgow last year parties created a work programme to “urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation” this decade. This year parties have been discussing how this programme would work, but effectively it will be starting from scratch in Egypt. It would be important for these discussions to progress at COP27, to achieve tangible outcomes, for example, by deciding on at least a work programme. It will be interesting to see whether Parties decide to again require a further ratcheting of ambition in NDCs by next year and to what extent Egypt can demonstrate leadership in relation to the ambition element of the Paris Agreement.

Global Goal on Adaptation

Countries will also be engaging on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) in Egypt. The GGA was established under the Paris Agreement, as a political compromise to elevate adaptation to that of mitigation, similar to the between 1.5 – 2°C mitigation goal. Last year Parties adopted the Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work programme on the GGA to support the development of a goal and means to measure it. Considerable progress has already been achieved this year during the workshops and a further one will be held during the COP. It would be important for African countries to see continued traction around a GGA and reaching consensus on what it might look like would be a considerable win for the continent. Having agreement on adaptation finance goals would also go a long way towards the implementation of the GGA.

Reform of the global finance architecture

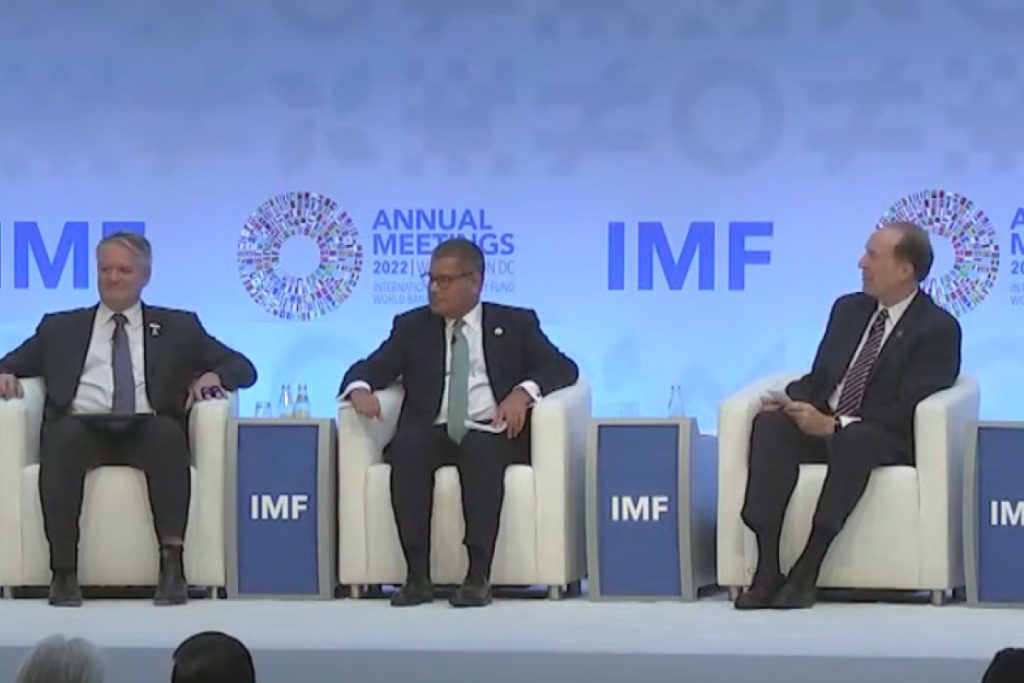

In the past year Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) including the World Bank, as well as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have been thrust into the spotlight for their role in relation to climate change. These discussions have been underway for a number of years, however they reached a crescendo this year, mostly as a result of the spotlight cast on the challenges developing countries have faced in accessing sufficient and fit for purpose climate finance, as well as the debt crisis many countries are facing after the pandemic. A number of fundamental reforms have been proposed on the role of the World Bank. A number of countries, including the IMF itself, are also looking at how the IMF can play a changed role both in the context of debt forgiveness/debt for climate swaps, and the reallocation of special drawing rights. These issues are likely to come to the fore again at the COP, particularly with the US pushing for attention to be focused on the role of MDBs in response to the questions raised about the adequacy of public climate finance. The US is not the only one and the African Group of Negotiators has also long pushed for the architecture of the MDBs to be revisited to make them fit-for-purpose, and for them to play a greater role in de-risking investments in developing countries.

To those going to this year’s COP in Egypt, we at African Climate Wire wish you much strength, wisdom, stamina and good health!