This week has been replete with COP27 reports and analyses, many highlighting the good and the bad, and most reiterating the refrain that it was a disappointment, none of which is unusual for post-COP feedback. This analysis also throws its hat in the ring, concluding that COP27 was a mixed bag, and whilst there were many disappointments from both sides, it should be celebrated for as a win by developing countries, marking the climax of a decades long battle for dedicated loss and damage finance.

COP27 was meant to focus on implementation and procedurally no key decisions were due to be decided. It was overshadowed by climate disasters, inflation, debt and energy crises, political instability, the lingering effects of the pandemic. The outcome of the second most attended and third longest COP was the Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan, that was gavelled into life, 36 hours late, on Sunday morning.

The negotiations were marked by the ongoing North South divide, with developing countries resisting pressure from developed states to make further commitments in the absence of a failure to deliver on their mitigation pledges and climate finance. Debates about the meaning of equity and the continued relevance of the foundational principle of common but differentiated responsibilities in light of respective capabilities (CBDR-RC), as well as the distinction of obligations between developed and some developing countries, notably China and India, have plagued negotiations for almost two decades. However, the pressure to revisit this distinction was particularly pronounced at this year’s COP, and continued to stymie progress on multiple fronts notably in the context of mitigation and finance.

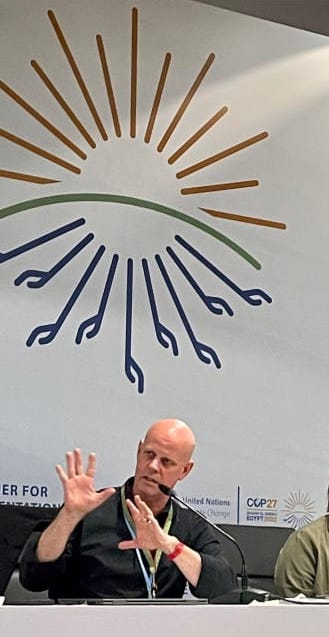

In the long-read that follows we attempt to capture some of the key outcomes of the COP, taken from a developing country perspective. Our views are captured based on insights from Climate Legal’s Andrew Gilder who attended the COP, the negotiated texts, and various formal and informal reports of the negotiations. For lightness, we have included Andrew’s photo diary of the COP, which does not do justice to the slightly dystopian feel of it all.

The cover text

As is often the case, it was the cover decision that took the longest to negotiate. For context, a COP decision text is not a treaty that is ratified or acceded to by national governments, and rather it gives flesh and detail to how parties interpret and intend to apply the Paris Agreement and UNFCCC. However COP texts are also important because they fall into the category of so called “soft law” that can be used to inform and guide binding decisions and which, in court, may be used to interpret the scope of a legal obligation. For that reason, amongst many others, while the Implementation Plan is not strictly binding, it has consequence and its wording is important in shaping future ambition and national responses.

During negotiations, developed countries were looking to see mention in the text of a commitment to a 1.5 degree future, timelines for emissions to peak and more ambition pre 2030, and for countries to have a more explicitly shared burden on climate action. Developing countries were looking to see text that reflected the CBDR-RC principle, timely finance, and stronger text on technology, resilience, energy access and capacity building. Least Developed Countries wanted to see more accountability mechanisms for existing pledges.

Some of the key provisions of the Implementation plan which in many respects, echo the Glasgow Pact include:

- a recognition that the 1.5C target “requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions reducing global net greenhouse gas emissions by 43% by 2030 relative to the 2019 level” (a reference in the Glasgow Pact to net zero by mid-century was not repeated. Note also that Glasgow has a slightly different baseline, being a target of 45 per cent by 2030 relative to the 2010 level);

- Retention of the call to phase down unabated coal power and phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies (as discussed below text to enhance the scope of this commitment was rejected by Russia and Saudi Arabia and Iran);

- Retention of the call in the Glasgow Pact for parties who have not yet communicated new or updated nationally determined contributions (NDCs) or long-term low GHG development strategies to do so by COP28; and

- developed countries were urged to provide enhanced support to assist developing countries to both mitigate and adapt, and encouraging other parties to provide or continue to provide support voluntarily.

Some notably new additions to the text included:

- the launch of the Sharm El-Sheikh dialogue on Article 2.1(c) to ensure that finance flows are aligned with the global temperature goal;

- establishment of a Just Transition work programme that outlines pathways to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement (the US had opposed this) with annual “high-level ministerial round tables”;

- a recognition of the need for “transformation of the financial system and its structures”, together with a call for multilateral development banks and international financial institutions to reform their practices and priorities to address the “global climate emergency”; and

- the mentioning of food, rivers, nature based solutions and tipping points and the right to a healthy environment was included in the cover text for the first time.

Loss and Damage

Discussions on loss and damage started with an “agenda fight” at the opening of the COP that lasted more than 48 hours. It ended with the inclusion of an agenda item for finance for loss and damage, subject to caveats inserted by the US that the inclusion of the item would not lead to any form of legal liability.

Building on a year of campaigning the rally cry of civil society and developing countries, as represented by the G77 plus China, was a call for a new funding facility with dedicated resources for loss and damage. Developing countries were looking for a clear agreement to establish such a fund in principle and have it operationalised as soon as possible, with agreement on its modalities and related considerations to follow in future. The position of the G77 plus China was that a committee could be established determine the arrangements of the fund for approval next year.

Whilst developed countries acknowledged the importance of such finance, they preferred for it to be addressed within a “mosaic” of solutions, such as through a funding “window” within the Financial Mechanism, and insurance. Indeed regional insurance gained considerable attention with the official launch of the G7’s Global Shield at the COP, which attracted the majority of loss and damage finance that was pledged during the negotiations. The EU felt that establishing a fund would take too much time. There was also a reluctance on the part of some developed countries, in particular the US, to engage in finance discussions in case they led to legal liability.

To the surprise of many, soon before negotiations on loss and damage finance were due to end, the EU reversed its position, stating that it would agree to the establishment of a finance facility for loss and damage, but with some important strings attached:

- First, it required that contributors should go beyond the list of countries defined as developed under the UNFCCC in the 1990’s and include other developing countries. In a statement on the 16th of November to reporters, the EU climate policy chief, Frans Timmermans said “I think everybody should be brought into the system on the basis of where they are today. China is one of the biggest economies on the planet with a lot of financial strength. Why should they not be made co-responsible for funding loss and damage?”;

- Another proviso of the EU was that agreement on the fund was conditional to all countries stepping up their mitigation efforts to peak emissions by 2025 with a commitment to keeping 1.5C limit in reach; and

- It also put forward that the fund should benefit particularly poor and vulnerable countries, and as yet undefined term.

Despite its historic reluctance, following the statement by Timmermans, the US also agreed to the in principle establishment of the fund, however it retained its position that such a fund would not invoke any liability or compensation.

Unsurprisingly the EU’s position stands at odds with that of the G77 plus China which felt that the fund, like all other UNFCCC funds, should be financed by developed countries Parties on the basis of the longstanding principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC), taking into account historical responsibility. China’s position is that the onus remains on developed countries to contribute, with low and middle income countries only contributing voluntarily, and with funds going to the most “fragile” countries first.

The proviso of the EU, sought to hold developing countries ransom to revisit these principles at the risk of losing out on the establishment of a fund. Fortunately the final text makes no mention of the need for developing country contributions or the need for enhanced mitigation action as a conditionality. It is equally silent on the obligation of developed countries to finance the fund.

Instead it provides for the establishment of a Transitional Committee that will make recommendations on the operationalisation of “new funding arrangements” for developing countries that are “particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change” for loss and damage, including the operationalisation of a fund for responding to loss and damage, ahead of COP 28 next year. Its mandate includes “identifying and expanding sources of funding” recognising the “need for support from a wide variety of sources, including innovative sources”, signalling the broadening of the contributor base away from developed countries and a possible shifting of the burden to other non-state actors. To this end the text also invites the IMF and World bank to consider the potential for them to contribute to the “funding arrangements”.

The text also makes no mention of CBDR-RC, but instead broadly just recalls the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement. Positively, however, it also recognises a broad range of different forms of loss and damage including non-economic loss and damage, emphasises that finance is for “responding to” (and not just minimising and averting) loss and damage, and it leaves open the question of whether a fund will sit under the COP (UNFCCC) or not. The hope is that if the fund sits under the COP it might not be subject to some of the legal liability disclaimer text for loss and damage under Article 8 of the Paris Agreement and its accompanying decisions.

As such, much will turn on the discussions in the Transitional Committee during the course of next year on whether developing countries will agree to being pulled into the finance regime for loss and damage, how “particularly vulnerable countries” is defined, and where the fund will sit. Given the resistance to date and positioning of China and India at the negotiations, agreement on developing country contributions is considered unlikely. If the expectation for them to contribute continues, potentially the fund may never see the light of day, putting into question the bona fides of the US and EU in agreeing to it in the first place. If this line of negotiating continues, it may also potentially fracture the cohesion and goodwill amongst developing countries that propelled the proposal by G77+ China on a loss and damage fund into the spotlight at COP26, particularly if SIDS are looking to see the establishment of a fund at any cost. Notwithstanding its complexity and uncertainty, the establishment of the fund in principle is a historic and momentous occasion, and certainly can be hailed as a historic achievement for developing countries, in particularly SIDs who have been championing it since the 1990s.

Another successful moment for loss and damage was the establishment of an Advisory Board to govern the Santiago Network. This was a key demand of the G77 and China (discussions were focused on whether the Network should have an Advisory Board, or simply provide advisory services, for example, by the existing Warsaw International Mechanism ExCom). A highly representative board was agreed to and it provide the technical assistance to communities to address loss and damage arising from climate impacts.

Mitigation

COP27 has been criticised for both failing to progress beyond what was agreed to at Glasgow last year and for setting forward a weak and ineffective response that will not achieve a 1.5 degree future. Others at the COP, however, were saying that, given the poly-crisis, it is a miracle there wasn’t more erosion of mitigation ambition in the text.

Temperature Goal

On temperature goals, some countries were calling for a reference for the need to stay below 1.5°C, whereas other countries wanted to refer to the full text of the temperature goals in the Paris Agreement to stay well below 2°C while pursuing efforts to limit long-term temperature rise to 1.5°C. Ultimately the Implementation Plan repeats the Paris text, but also holds the line of 1.5 degrees, acknowledging that this necessitates “rapid, deep and sustained reductions… by 43% by 2030 relative to the 2019 level”.

There was also a push by developed countries to have a peaking of emissions by 2025 in pursuit of the 1.5 degree limit. Whilst the peaking of emissions is important from a climate perspective, it was perceived as a push to shift the onus onto developing countries and a new form of commitment by them, as most developed countries have already peaked their emissions. The question then became which countries bear the primary responsibility of reducing emissions overall and how to divide up the global carbon budget equitably. Developing countries were particularly resistant to this proposal as they felt that developed countries had themselves failed to honour their own mitigation ambitions and related pledges over the past year. As such it was about the equity of the process and which countries should take the deepest emission cuts in the short term.

Actions before 2030: Mitigation Work Programme

To meet the global temperature target countries also focused on how to structure the mitigation work programme agreed to in Glasgow last year to “urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation in this critical decade” (Mitigation Work Programme). At the beginning of the negotiations, developed countries were apparently seeking to have the top twenty emitters, including China and India, commit to drastically reducing their emissions, and that this would be irrespective of developing country status. This was met with resistance from India, with support of like-minded developing countries, including China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan, on the basis that it would lead to a reopening of the Paris Agreement, and the principle CBDR-RC. Coming into COP27, developing countries had raised concerns that rich nations, through the Mitigation Work Programme would compel them to revise their climate targets without enhancing the supply of technology and finance. In the run-up to COP27, India had said the Mitigation Work Programme could not be allowed to “change the goal posts” set by the Paris Agreement.

Developing countries sought to have the principles of CBDR and equity included in the text as well, but this was not agreed to. Switzerland, for example, stated that equity should either be excluded from the Mitigation Work Programme or there should be a clause requiring major emitters, such as China and India to have “special responsibility” to scale their mitigation efforts. Parties also struggled to agree on whether there should be dedicated sectoral or thematic timelines, targets or benchmarks.

It was ultimately agreed that the work programme will be non-prescriptive, non-punitive, facilitative, respectful of national sovereignty and national circumstances, take into account the nationally determined nature of NDCs and will not impose new targets or goals. Instead the scope of the work programme will be based on broad thematic areas relevant to urgently scaling up mitigation ambition and implementation. Since there is no identification of new targets, CarbonCopy has noted that the text effectively means that the Mitigation Work Programme will only help in identifying sectors on which work can be done and how those are reported through 2026.

On time frames and actions before 2030, two developing country groups called for the work programme to conclude in 2023 to avoid a duplication the global stocktake. Other developing countries together with developed countries wanted to seek work continue until 2030, given the mandate to focus on the decade. It was also decided that the implementation of the work programme would start immediately and continue until COP28 next year, with a view to deciding its continuation at that session.

On the side-lines, however, the Breakthrough Agenda was launched by a coalition of countries representing 50% of global GDP. The Agenda is a package of 25 collaborative actions that will increase decarbonisation across the sectors of power, road transport, steel, hydrogen and agriculture. The will be extended to buildings and the cement sector next year. It seeks to build on the commitments made at COP26 by 45 countries to accelerate climate action in key sectors.

Fossil Fuel Phase Downs

In relation to fossil fuels, COP26 had agreed to phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. The Indian delegation, supported by broad coalition of more than 80 countries, continued its pursuit for the broadening of the existing language to include all fossil fuels. As a positive sign, and contrary to last year, for once the US did not oppose this position, it was only Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iran that did, which led to the position being left out of the final text. There were concerns that the Egyptian Presidency had not done enough to ensure that the revised text found its way into the negotiated text.

The final text that was agreed continues to promote renewable energy but now also includes “low emission” energy, which is broadly being interpreted as a “loophole” to promote gas and nuclear or possibly fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage technologies.

Finance

The topic of climate finance dominated last year’s negotiations, as it has every year, with a particular focus on the extent to which developed countries have lived up to their pledge to provide US$100 billion annually in climate finance. It was hoped that developed countries would make good on their historic shortfall but the current text simply expresses serious concern on a failure to meet the target and urges developed countries to meet the goal. No-one reacted warmly to the statement by US Climate Envoy on the current level of climate finance: “It’s at $90-something…when I got 90-something on a test at school I felt pretty good.”

While developing countries sought to highlight the need for urgent action and offer more prescriptive language, developed countries wished to see language that noted where progress had been made, for example in its replenishment of the Adaptation Fund and the Global Environment Facility. In the end, the final text welcomed progress that had been made with these funds, requests reports on progress achieved in meeting the $100 billion target and simply acknowledges the lack of a common definition of climate finance. Unfortunately the lack of a common definition means that developing countries will still continue to battle with vague and unclear and inconsistent approaches to determining how developed countries have met their pledges.

Parties also discussed the new quantified goal on climate finance that is to be agreed before 2025. South African co-chair of the standing committee on finance sought a target of between $1-2 trillion. By contrast, developed countries felt it was premature to consider a numerical quantum. Unsurprisingly developed countries also continued stress the role for the private sector and an expanded group of donor countries. Whilst many developing countries don’t oppose more private sector finance, they feel it is a distraction from the obligation of developed states to provide catalytic and adequate forms of grant finance. As a representative of LDCs stated pithily to CarbonBrief: we are looking for grants, and grants do not come from private finance. Ultimately the agreed text does not progress matters further and negotiations on the topic will resume next year.

Just energy transition partnerships (JETPs), first launched with the South African deal at COP26, also gained notable attention at the COP with the launch of the South African JET Investment Plan, and a $20 billion JETP for Indonesia. It has been described as the largest climate finance transaction to date. JETPs also made their way into the COP27 cover decision as an example of a “cooperative approach” to mitigate emissions.

A positive step of this year’s COP is its focus on the financial sector. The cover text recognises that delivering on funding will also require a transformation of the financial system and its structures and processes, engaging governments, central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors and other financial actors. This was a particular ask that African countries had sought to achieve out of the COP. Another win for African countries and developing countries more broadly, is that the text also calls upon shareholders of MDBs and international financial institutions to reform MDB practices and priorities, align and scale up funding, ensure simplified access, and to deploy a wider range of instruments in a manner that takes debt burdens into account, amongst other material reforms.

Adaptation

Although pledges worth US$230 million were made to the Adaptation Fund, negotiations on adaptation commenced with concern that historic pledges to the fund were unfulfilled. The Third World Network, represented by South Africa, for developed countries called on developed countries to make good on their pledges made last year to the Adaptation Fund, stating that blaming slow budgetary cycles was an incomplete and poor response. South Africa also disputed the role of the United States in the informal negotiations on the fund, and it was decided that the US should not participate given that they are not a party to the Kyoto Protocol, under which the fund is established.

Developing countries were also looking for a substantive outcome on the global goal on adaptation at this year’s COP and sought the establishment of a framework to guide the development of the goal. This came amidst concerns by developed countries that there was insufficient time to consider this point. Ultimately, and to the pleasure of developing countries, parties agreed to establish a framework as a long term structured effort to help deliver the goal and track progress towards it. In an interview with CarbonBrief, director of the Red Cross Climate Centre, Prof Maarten van Aalst stated:

“For those people that came from the mitigation world and wanted a simple target – like a temperature target – for adaptation, it was never going to happen. I do think the framework text that we have now has many of the right elements, it has many of the right linkages to IPCC science, which is a really good starting point”.

In a parallel move, the COP Presidency also launched the Sharm El Sheikh Adaptation agenda. The agenda also outlines 30 Adaptation Outcomes to enhance resilience for 4 billion people living in the most climate vulnerable communities by 2030. Possibly this agenda seeks to model a prototype of what a global plan of collective adaptation goals could look like.

The Africa Group was also seeking for the IPCC to provide a special report on the global goal for adaptation, however parties ultimately didn’t agree to this because of the heavy existing workload of the IPCC.

African countries were also looking to see an express commitment to the doubling of adaptation finance, as agreed to last year. It was hoped that a clear implementation plan would be agreed to make up for the shortfall, however, these provisions did not make it to the final text and instead the Standing Committee of Finance is to prepare a report. This comes in the wake of a request by the African Group for a dedicated COP27 agenda item on doubling adaptation finance being denied.

Agriculture and Food Security

Hunger, agriculture and food security were also expected to be a big topic at this year’s COP as a result of the energy crisis and war in Ukraine. The Koronivia Joint Work for Agriculture working group which has the mandate to engage on agricultural vulnerability and approaches to improving food security was given a further four year life span. This leaves agriculture as the only dedicated “sector” with its own negotiation track in the UNFCCC. Parties however could not agree on a roadmap for the future of the work programme. There were also debates on whether to include a ““whole of food system perspective” within the scope of discussions, with developed countries in support, but others having concerns that this would raise the difficult issue of consumption and diets. The final text agrees to a four year timeline for the programme, and reference to “food systems” has been generally avoided in the text.

Carbon Markets

Article 6 is a highly complex and technical provision and we at Climate Wire will unpack the COP decision texts for African audiences in the coming weeks and months. In brief, we note some of the high level developments here.

Although parties agreed on a rulebook for Article 6 (which governs carbon markets) last year, further decisions were still required to fully operationalise it. At this year’s COP, the parties provided operational guidance for cooperative approaches under Article 6.2, although the full procedural rules still need to be resolved. Issues discussed at this year’s COP included what information needed to be reported on trades and what could be kept confidential. Another issue which will be dealt with at next year’s COP is how to link up infrastructure to create a centralised accounting and reporting platform.

Article 6.4 discussions on the trade of carbon credits progressed. The negotiations were preceded by decisions by the Article 6.4. Supervisory Body to allow for credits for emissions (engineered or natural processes that remove carbon from the atmosphere). In response to concerns on this decision, parties at the COP directed the supervisory body to engage more on the issue. A decision was made also on how to deal with Article 6.4. credits issued without authorisation for use towards the buyers regulatory requirements.

Stocktake and looking ahead

The global stock take is scheduled to take place every five years under the Paris Agreement. Its purpose is to take stock of the extent to which Paris has been implemented with the goal of assessing collective global progress towards achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement. It assesses mitigation, adaptation and the means of implementation (including finance). The stock take ends just before countries are supposed to submit their revised NDCs in 2024, and is supposed to inform the content of those NDCs, by ratcheting up their ambition.

As such, next year’s COP in Dubai will focus on the global stocktake, and most likely have a strong emphasis on assessing implementation. Some have predicted it will also have a mitigation focus, and possible also a carbon removals focus. In the final text, the CMA reminds parties to submit their first biennial transparency report and national inventory report by the end of next year.

This year’s COP, marked the end of the technical information gathering phase of the global stock take, and the beginning of the political phase. It bodes well that at COP27 technical dialogue on the global stocktake proceeded seamlessly, framed mostly as a dialogue between countries, climate experts and civil society. Countries were invited to next year “hold events, at the local, national, regional and international level, as appropriate, in support of the global stocktake”. Whilst this will have budgetary implications, it will no doubt help engender public awareness and involvement in national climate policy, and better prepare the public for the upcoming revision of NDCs. The UN Secretary General will also host a “climate ambition summit” ahead of the first global stock take next year.

Takeaways

We join the celebrations of other reporters in the achievement of a loss and damage fund, this was hard fought and hard won. Much of the devil will be in the detail and developing countries will need to continue to diligently ensure that the fund is established on equitable terms that ensures its speedy operationalisation.

Whilst certainly there is much disappointment around a lack of progress on finance, mitigation, and fossil fuel phase downs, these coalesce around a long standing dispute between developed and developing country party distinctions that have ever plagued the negotiations. Potentially there is hope to be found in the renewed relations between China and the United States, and some of the positive statements coming out of the heads of state at Bali’s G20 summit this week where countries resolved to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.

We are reminded that the UNFCCC COPs are no longer the sole forum for climate multilateralism and that discussions and decisions on all of the issues set out above are taking place within multiple forums and in different contexts, from the WTO, to the UNGA, the G7 and G20 summits, the meetings of the MDBs and within the courts.

Whilst this year’s COP may not have delivered on all fronts for African countries, there are multiple entry points to pursue climate multilateralism, and we will continue to watch and report on these at Climate Wire.