Beyond extraction: Africa’s US$29.5trillion reckoning

Critical minerals like copper, cobalt, nickel, and lithium, fundamental to renewable energy systems and emissions-reducing technologies, are central to development. The increased demand for these minerals is expected to be complemented by traditional materials such as aluminium and steel, for technologies that enhance energy efficiency and transitions. Africa is thought to hold 30 percent of these critical minerals, valued at approximately US$29.5 trillion, with more than US$8.6 trillion underdeveloped. Its mineral wealth also provides it with an opportunity for local beneficiation and industrialisation.

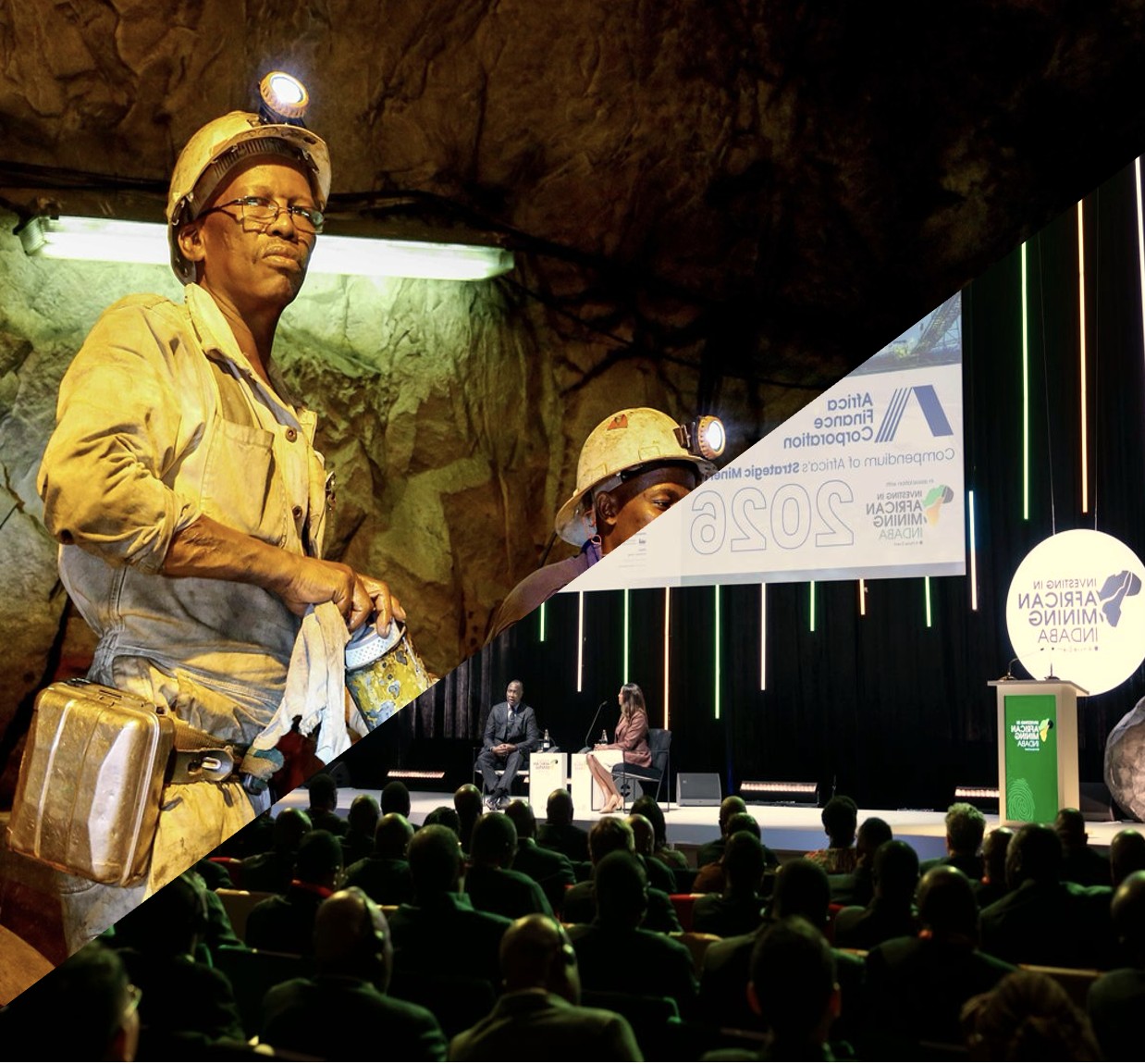

Against this backdrop, the 2026 Investing in African Mining Indaba, one of the world’s largest mining conferences, took place this year on 9-12 February, with governments, investors and industry leaders seeking to do one thing: influence mineral supply chains into the future. On the agenda was the launch by the African Finance Corporation (AFC) of the US$1billion compendium of strategic minerals, which maps the African mineral value chain. It was arguably one of the most compelling outcomes of the discussions, as it positions Africa for a competitive critical minerals race in a shifting geopolitical context, and sets out opportunities for finance for the region’s energy transition, which has been a moving target over the last few years.

Elsewhere the World Bank Group was touting its support to Africa’s minerals and metal value chains, while the EU pushed for an alignment of its mineral strategy with that of Africa, through a material cooperation engagement, and a reimagination of mining partnerships through empathy.

One thing was clear, African countries were making a case for how to leverage the rise of new investors in critical minerals and showcasing projects through numerous exhibitions. There were nearly 40 panel discussions and presentations by countries across the three-day period devoted to capital mobilisation and investments.

A minerals paradox across five ‘Africas’

Despite its geological diversity, East Africa, the AFC argues contributes only about 2.5 percent of current mine site value, including its critical mineral value chains. Critically, it has the world’s most cost-efficient exploration, spending approximately US$55million per discovery, compared to an average of about US$119 million elsewhere. Through Rwanda and Tanzania, the region could create new refineries, shared infrastructure and value addition plans, that benefit the region.

In Central Africa, the tussle is between developing natural wealth and severe infrastructure fragmentation. This has led to calls for more coordinated infrastructure investment, and scaled projects that actually work, such as the trans-Gabon railway and CAMRAIL Corridor. These could unlock cross border resource development to anchor low carbon critical mineral processing at scale.

Southern Africa on the other hand holds more than half of Africa’s operating mine value, but recent de-industrialisation pressures – rail underinvestment, power constraints, and subdued demand, particularly in South Africa have idled processing. The region, the AFC argues holds deep institutional capacity, port linked industrial zones and the most integrated power pool that offers an opportunity for re-industrialisation.

In West Africa, the opportunity for developing critical minerals lies in shifting from a fragmented, enclave-style pit-to-port extraction towards regional industrial aggregation. This will require mobilising the region’s hydropower and gas resources, synchronising the West Africa Power Pool, development of alumina refineries in Guinea and Ghana, building multi-user rail and logistics corridors, and investment in systems to discover underexplored geological endowment.

North Africa holds potential through its robust infrastructure – rail, deep water ports, and significant processing capacity. But its critical minerals development relies on large imports of feedstock. According to the AFC, to bridge this material gap, the region must align new developments in mines to existing processing infrastructure, while simultaneously leveraging the renewable energy potential to drive a green industrialisation agenda to decarbonize its processing value chains.

Across all five regions, a common imperative emerges: the future of Africa’s critical minerals industry hinges not on extraction alone, but on deliberately building the cross-border infrastructure and regional value addition systems that can transform geological endowment into lasting industrial capacity. This is the central theme of Africa’s Green Minerals Strategy (AGMS). This is a function of investment, and who bells this cat?

Billions behind schedule – foreign mineral finance floods Africa but still falls short

The finance for critical mineral projects is predominantly foreign and comes in the form of loans. It is also susceptible to geopolitical flux, clear from the approximately 42 percent decline of foreign direct investments in Africa last year. China in 2025, through its policy banks issued loans in the region of US$24.9billion, for critical mineral projects in Africa. These instruments are akin to most development finance instruments, with features including: offtake agreements that guarantee future mineral deliveries regardless of owners; farm-in contracts that fund exploration for future production rights; leasing deals that supply technology and equipment for fixed periods, and outright acquisitions. They are extractive, but contribute to building much needed extractives infrastructure compared to finance from other jurisdictions.

The European Union, following on from its Critical Raw Minerals Act, made some commitments to the development of mineral value chains, in Africa. In South Africa, it announced a €4.7billion financing package for mineral processing, green hydrogen and transport infrastructure, additional deals for Cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and a €461million iron ore export facility and infrastructure finance in Mauritania. Under its Global Gateway initiative, it plans to invest approximately €150billion in Africa by 2027. It is unclear today, how much of this target has been achieved, and some have queried whether it would include new and additional funding or simply be a reallocation.

Prioritization of finance – America’s playbook

The US government is orchestrating a multi-agency financial strategy to build resilience in critical minerals, deploying US$35billion in total public financing, leveraging loans, equity commitments and strategic initiatives to crowd in private capital and prioritise security. From the Department of Energy’s US$8.9billion in loans and commitments for domestic lithium, graphite and potash projects, through USEXIM’s US$11.9billion for strategic mineral reserves, and USDFC’s US$1.3billion for international mineral exploration deals, it is clear that they intend to use public funds as a catalyst to unlock private capital, to finance everything from mine to magnet, with a view to retain value.

How Africa’s own vaults can stop the mineral wealth leakage – a $1trillion question

The argument has been made that the external financing results in benefits that should be accruing to African countries, leaking overseas, unless countered by local capital market development and adequate instruments that mitigate currency risks.

The Green Minerals Strategy of the African Union, under the auspices of the African Minerals Development Centre (AMDC) indicates the need for a Green Mineral Value Chain Investment Fund (GMVCF), and the development of local venture capital funds. The GMVCF would need to ensure that funding for foreign mining companies is linked to proportional mineral export rights, and they would need to be capitalized by institutions like the African Development Bank, Afreximbank, and Just Energy Transition funds.

For context, African state-owned institutions now manage about US$1trillion in assets, with a majority of these funds held by public pension funds and central banks. Sovereign wealth funds are also experiencing rapid growth, with the Libyan Investment Authority holding more than US$68billion, and five new funds launched in 2025 alone in the DRC, Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya and Nigeria. These provide a good buffer against geopolitical tensions, high interest rates, and reinforce the need for domestically managed assets to catalyse investments in critical mineral value chains and supporting infrastructure.

As Africa stands at the crossroads of possessing US$29.5 trillion in critical mineral wealth while watching US$8.6 trillion remain underdeveloped, the 2026 Mining Indaba made clear that the continent’s future hinges on moving beyond extraction toward deliberate industrialisation. Yet the current reality reveals a paradox: while foreign finance floods in, these instruments remain predominantly extractive, prioritizing offtake agreements and export rights over local value retention. The AFC compendium of strategic minerals and the African Union’s Green Minerals Strategy and its GMVCF offer a roadmap, but they require capitalisation from within. Fortunately, Africa’s state-owned institutions now manage US$1 trillion in assets. The question is no longer whether Africa has the resources or the institutional capital, but whether it can strategically deploy its own vault to finance the cross-border infrastructure and regional processing systems that transform geological wealth into lasting industrial power.