The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is a border tariff on imported goods based on the carbon price in their country of origin, and is one of the EU’s principal mechanisms to achieve its climate goals. Its objective is to equalise the price emitting EU companies currently pay for their carbon emissions under the EU’s emissions trading scheme (EU ETS), with those of imported goods. The design of the CBAM is still under refinement, however its transitional phase will commence in October this year. Early analyses indicate that the CBAM will negatively affect developing countries more than developed ones, and that the impact on African exports may be considerable in some sectors.

At a recent webinar hosted by the South African Presidential Climate Commission on the potential implications of the CBAM, London School of Economics’ Professor Dave Luke cautioned that African countries were highly exposed to the CBAM since 26% of continental trade was with the EU, while only 2.2% of the EU’s trade was with Africa. Citing research commissioned by the African Climate Foundation which is currently underway, he warned that, the CBAM could reduce Africa to EU exports by up to 5.7%, based on current carbon prices. This may have the effect of reducing Africa’s GDP by 0.91%, which is “equivalent to an about $16-billion reduction in GDP at 2021 levels.” Luke highlighted that the full impact of the CBAM would be dependent upon the price of carbon and its final design, including the scope of products it applies to. It would also depend on how quickly it is phased in and whether the EU eliminates the allowances it currently provides to EU producers under its emissions trading scheme.

Luke commented that “Africa is likely to be more severely affected because we are more exposed than most other countries or regions, such as China or India. This is due to the fact that production in Africa tends to be more carbon intensive – so it will suffer a greater competitiveness shock – and because there is a relatively higher proportion of exports going to the EU.”

When proposing the CBAM the European Commission’s own analysis predicted that the it may reduce total exports from African countries by up to €4.1 billion. Another analysis suggest that, subject to the actual carbon price used, Sub-Saharan African exports to the EU could fall by -8.9% for chemicals; -0.5% for aluminium/non-ferrous metals; -18.8% for iron and steel; and -19.9% for cement/non-metallic metals in 2030. Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Cameroon are some of the most exposed countries, although Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and South Africa also stand to be significantly affected.

At the webinar, University of Cape Town adjunct Professor Faizel Ismail, who previously served as South Africa’s ambassador to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), doubted the legality of the CBAM, and whether it violated the WTO rules around the most favoured nation principle.

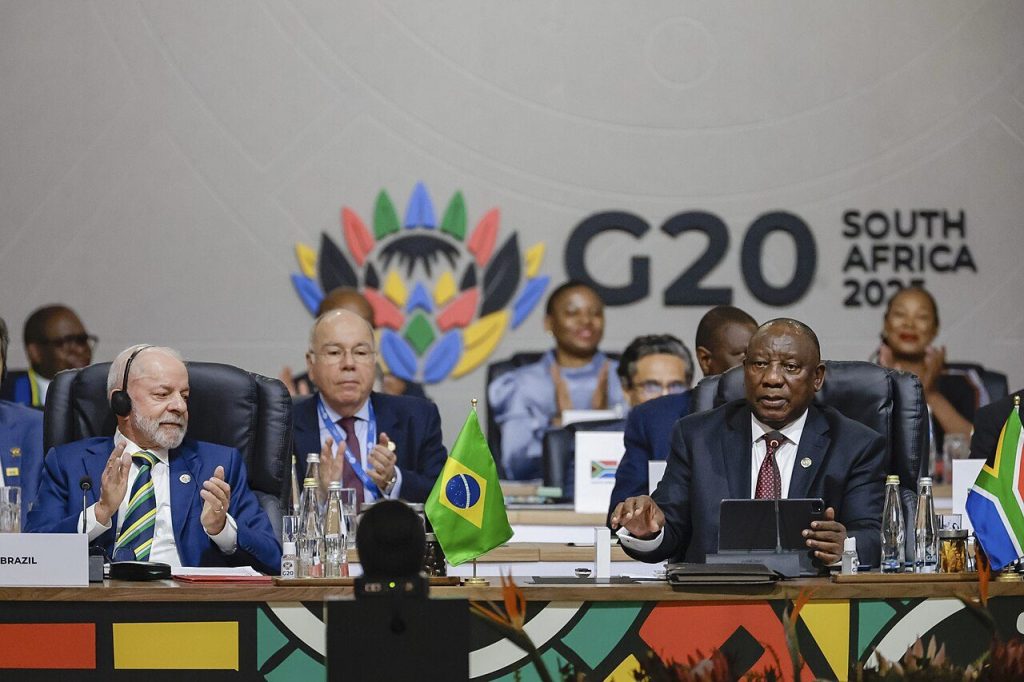

He argued, that the CBAM should be viewed within a wider context of moves by blocs and countries, including the United States and China, to bolster green industrial competitiveness. In his view, developing countries need to group together to fight the CBAM and related protective measures, predicting that there would be an increase in litigation on climate related issues at the WTO. He argued that “we should be demanding that the EU, the US, China and others really engage at the multilateral level, as there needs to be greater coherence between the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the WTO and the G20 on finance and how we can collectively avoid ‘war games’ in the climate space or the green space and really begin to engage how we can cooperate to work together towards a lower-carbon and more sustainable world.”

The webinar comes just as the AU concluded its 36th Assembly, the theme of which was the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). At the Assembly the AU underscored the urgency of operationalising the AfCFTA, and the importance of free trade to the continent’s developmental aspirations. The AfCFTA creates the African Continental Free Trade Area, one of the largest such areas by population and geographic size. As members of the AU and regional economic blocs engage with their trade counterparts at the WTO, it would be important to engage with the CBAM to avoid the war games that Ismail refers to, but also to simultaneously capacitate African Regional Economic Communities to better understand the anticipated impact of the CBAM and incorporate climate considerations within the forthcoming protocols under the AfCFTA.