As countries convene in Bonn for the more technical 62nd session of the UNFCCC’s Subsidiary Bodies, they will need to make progress on outstanding issues that could not be resolved at COP29 last year in Baku. Included in this list is how to implement the Global Stocktake which was concluded at COP28 in 2023 and is meant to be one of the primary catalysts for enhanced ambition and strengthened NDCs.

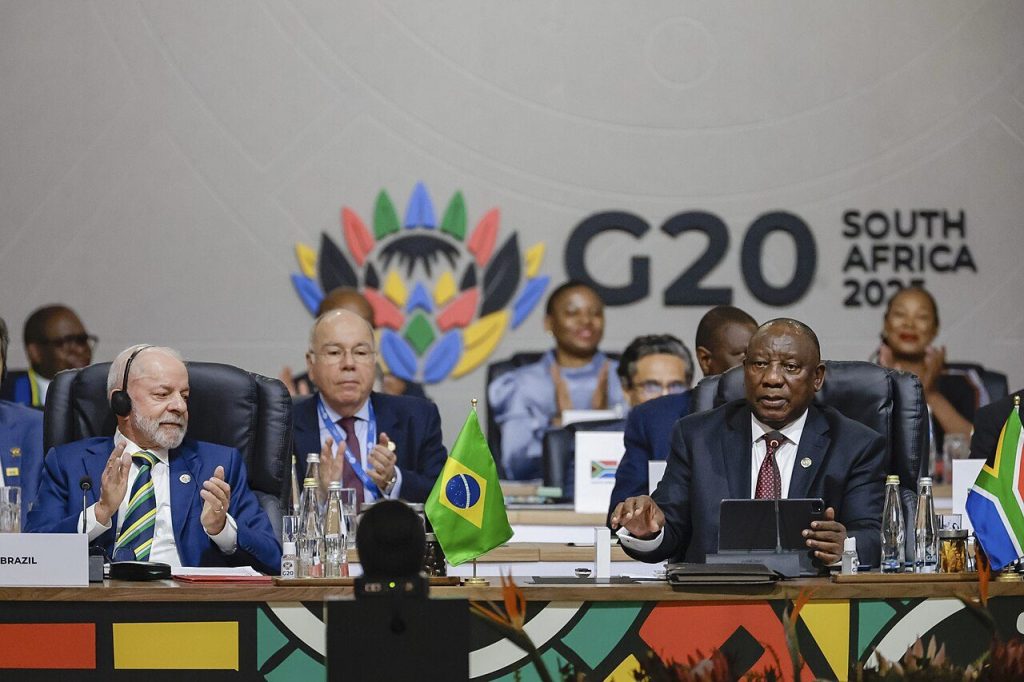

Before they do so, they will first need to resolve the agenda, with the second day of the meeting opening with no consensus on whether to include new agenda items on the duties of developed countries to provide climate finance (implementing Article 9) and trade related measures like the CBAM. It has been difficult for the Brazilian COP Presidency to trim the agenda down to make it lighter and more implementation focused, with the co-chairs confirming there were already 50 agenda items for the meeting.

A spokesperson for the U.S. State Department also confirmed that they would not be sending a delegation this year, making it the first time in 30 years the US has not attended. It is, however, also unsurprising given the country’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement earlier this year. What will be interesting to see is whether their absence leads to new configurations and whether some of the opposition seen to date, particularly when it comes to financial proposals, will either weaken, redistribute or be championed by those seeking to fill the gap.

This year, the co-chairs of the meeting are looking to prioritise: the finalisation of indicators to measure progress on the implementation of the global goal on adaptation, the Just Transition Work Programme, and various other matters such as the gender action plan, and work programme for mitigation ambition and implementation. Chief within this list is finalising next steps on how to implement the Global Stocktake and a decision on modalities for a dialogue on this topic.

Ever since it was finalised at the end of 2023, countries have been at odds on how to implement the first Global Stocktake. The stocktake is a landmark decision that assesses the state of global climate action and the implementation of the Paris Agreement. It is an outcome of a multi-year negotiated process, including both technical and political input. Working on five year cycles, the parties are already preparing to start the next one in 2026 with a view to finalising it in 2028. But the question for now is how to give effect to the 196 paragraph highly detailed first stocktake from two years ago.

The Paris Agreement requires successive NDCs to be “informed” be the stocktake. The next round of NDCs are due for submission this year, ahead of COP30 and countries have been scratching their heads on how they are supposed to reflect and respond to a negotiated document that represents a compromise of an extensive multitude of views, positions and findings, some of which they are more aligned with than others.

At the end of COP28 in 2023 in Dubai, countries agreed to initiating a process to implement some of the stocktake’s outcomes under the banner of a formal dialogue. Some developing countries have been pushing for the dialogue on its implementation to only focus on finance, because it sits under the “finance” heading in the agreed text. On the other hand, developed countries want it to address all outcomes of the stocktake. Last year saw no consensus on this issue, despite a near agreement on text that would allow dialogue in “parallel tracks” on the full scope of the Stocktake’s outcomes. Developed countries rejected it at the closing plenary because it did not include provision for an annual report on the progress of implementation, particularly on the fossil fuel transition. This speaks to a broader challenge: how will countries monitor some of the Stocktake’s more ambitious outcomes (that do not feature anywhere else in agreed texts) such as tripling renewable energy and doubling energy efficiency, the deployment of transitional fuels; and ending deforestation by 2030?

At the June talks parties will need to overcome their differences and address these issues, while agreeing to the dialogue’s modalities and how it is intended to work with other best practice and knowledge sharing annual discussions that were proposed in the stocktake outcome. Once agreed they then need to work on a draft text so that it can be finalised and ready for adoption at COP30 in Belém. Either way this will be too late for this year’s round of NDCs, although the first stocktake can inform the next round. It highlights a flaw in the iterative and cyclical process envisaged by the Paris Agreement: if one negotiated outcome fails or is significantly delayed it can cascade and negatively affect others. For now African countries will have to sit with the 196 paragraph text and decide for themselves what it means and how to incorporate it in their NDCs.