After a six year gestation this week finally heralded the enactment of South Africa’s Climate Change Law, following President Rhamaphosa’s signature and assent on Tuesday. The Act could not have come sooner, as the country has battled a slew of droughts, tornados, floods and other extreme weather events in the past few years.

South Africa follows in the footsteps of Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, and Mauritius and some 60 other countries worldwide that have enacted direct climate laws, covering approximately 53% of global GHG emissions. While none of these laws are the same, the South African Act offers something a little different.

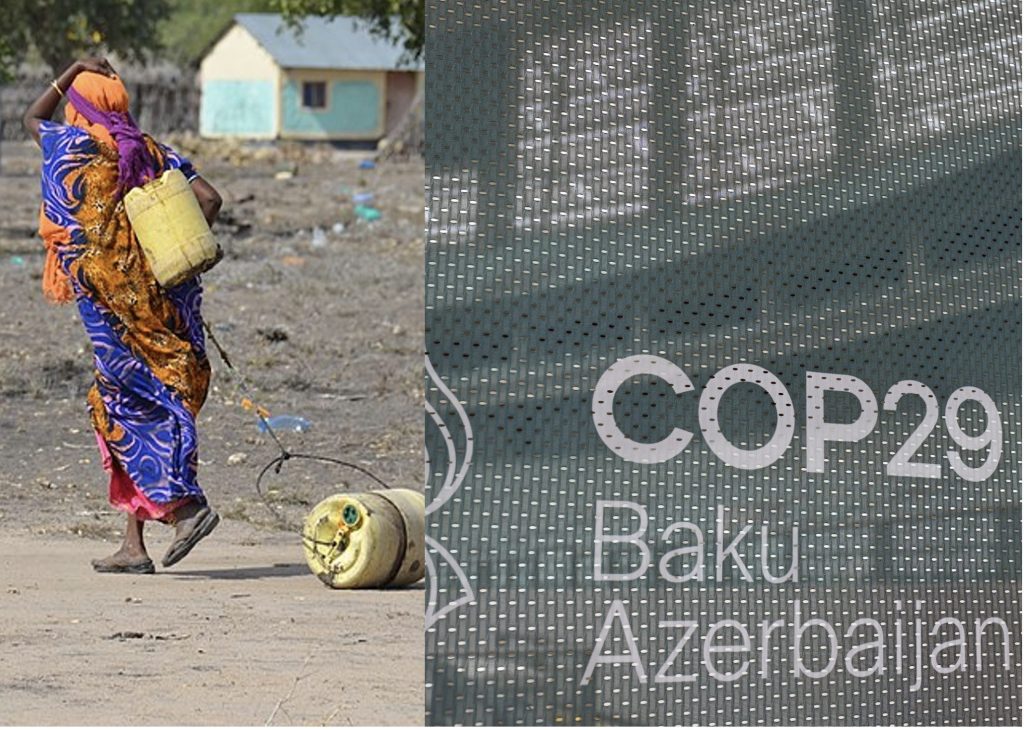

First, like many African climate laws (and unlike many in the global North), the Act is heavily weighted with adaptation provisions. Adaptation has long been a national climate policy priority, and the Act goes to great length to formalise an iterative process that shapes this policy by calling for a National Adaptation Strategy and National adaptation objectives and scenarios. While South Africa already has a strategy, the law ensures that it receives regular attention and revision and is not left to stagnate and languish like the many policy documents that have come before it.

The Act also entrenches the national greenhouse gas emissions trajectory into law. Not many climate laws do this. In doing so it identifies the Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment (Minister of Environment) as the person to set the trajectory in consultation with Cabinet. It effectively empowers that office with the mandate to set the development blueprint of the economy and the extent of its decarbonisation pathway, elevating the status of the Ministry above the traditionally meek role often occupied by the Environmental Portfolio.

It is this trajectory that then informs and guides the development of Sector Emission Targets that are to be allocated by the Minister to various emitting sectors of the economy, such as Energy, Transport, Industry and Agriculture. Again, while the Minister must consult with the affected Ministers of each sector, he has a pivotal role in determining the decarbonisation trajectory of that department. This is particularly relevant in South Africa where the Department of Electricity and Energy’s (DoE) coal expansion plans and carbon intensive electricity sector have long been the problem child of the green transition. While the nation is seeking to implement a Just Transition with various international partners (JETP), wavering plans by the DoE to delay the decommissioning of the country’s coal power plants and longer term plans to expand the coal baseload have destabilised the JETP’s investment plan. A Sector Emission Target for the DoE will not fix the country’s energy woes overnight, but, depending on its ambition, it has the potential to reign in any coal expansion plans and ensure that all sector departments align themselves with the national trajectory.

Party politics will also come into play. Newly appointed Minister of Environment, Dion George, representing the opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, in the freshly minted post-election coalition government, will have the unenviable task of formulating a sector emission target in consultation with Minister of Electricity and Energy, Kgosientsho Ramokgopa, from the incumbent African National Congress/ANC. Ramokgopa has demonstrated an increased appetite for renewable energy, as compared to his predecessor, however, the energy mix remains uncertain as the country battles continued power outages, low generation capacity and a constrained transmission network. In setting the energy department’s emissions target, and indirectly the energy trajectory of the country, George is legally obliged to balance socio-economic considerations with what is required by science when setting the target, a difficult task, given the coal value chain directly employs over 200 000 people. No doubt tensions in the newly formed government of national unity will come to the fore as each party seeks to put forward its vision for the timing and manner of the country’s energy transition. The Climate Change Act will play a determinative role in who gets the casting vote in this decision.

The Act also orientates itself as a mechanism to organise coordinated government action across the local, provincial and national spheres as well as across departments. It does this through a popular climate legislative tool, known as “climate mainstreaming”. Instead of crafting new instruments, existing ones are repurposed. Local governments are required to include climate assessments and response plans in their existing planning instruments (known as IDPs) and provincial governments are tasked with the same. National Departments that have sector emission targets must incorporate mitigation policies and measures within their existing plans. And there is a general requirement that any organ of state significantly affected by climate change, or which has a function that relates to it, must review and revise their policies, laws, and decisions to take climate change considerations into account. How local government will give effect to these obligations remains to be seen, and an ongoing concern has been their capacity and financial wherewithal to implement the Act. In the later stages of drafting an oblique and cryptic provision that provides for the establishment of a “financial mechanism” to support the nation’s climate change response was included, but little is known about what this would entail at this stage. The Act also lacks any reference to budget tagging or finance strategy, which is common in many of the climate laws being enacted in other parts of the world.

Lastly, the Act finally provides a legal basis for the continued operation and – importantly – financing of the Presidential Climate Commission. This 25 member body of government, labour, civil society, traditional leaders, local government and business representatives, was established two years ago but has been hampered by a lack of funding and legal mandate. The Commission has a broad role of advising on the nation’s climate change response. Its membership is so wide that it is unlikely to play a meaningful role in resolving any inter-departmental deadlocks (a role often undertaken by Climate Councils in other countries). However, it follows the long South African tradition of consensus driven debate and lekgotla, aimed at ensuring stakeholders are included in the transition dialogue throughout the journey.

The Act can rightfully be critiqued for lacking firm emission reduction quantitative targets, and for imposing weak penalties on corporate entities that exceed their prescribed carbon budgets. But what it lacks in teeth, it makes up for in equal measure in its substantive provisions on adaptation, sector targets, generous principles and cooperative governance. Many will breathe a sigh of relief that the country can now get going with the policy measures it has planned but lacked the legal mandate to implement since 2011. With those now in place, the government can swiftly move towards implementation. Citizens might have to wait a little longer, however, as the President still needs to fix a date for the law to come into force, something that will only likely happen once the Department of Forestry Fisheries and the Environment finalises the relevant regulations under the Act.

The law also gives the signal to the international community of the country’s commitment to its emissions reduction trajectory, the firmness of its intentions to implement planned adaptation actions, and a model of how adaptation objectives can operate at a national level. Hopefully in turn, it will catalyse climate finance investment in the way that many climate laws have done across the world.

*Olivia Rumble co-led the drafting team of the first iteration of the South African Climate Change Bill.