This year, the United States reneged on the $4 billion in pledges it had made to the Green Climate Fund, the United Kingdom recently announced a 40% cut in aid in order to finance its defence budget, and Belgium, France, and Germany announced significant aid cuts, including aid to countries stricken by climate disasters. With a lacklustre climate finance goal agreed at COP29 last year, and dwindling aid and development finance, it is unsurprising that African governments have continued to maintain relationships with their non-Western counterparts, as they seek a more equitable balance of power within climate negotiations.

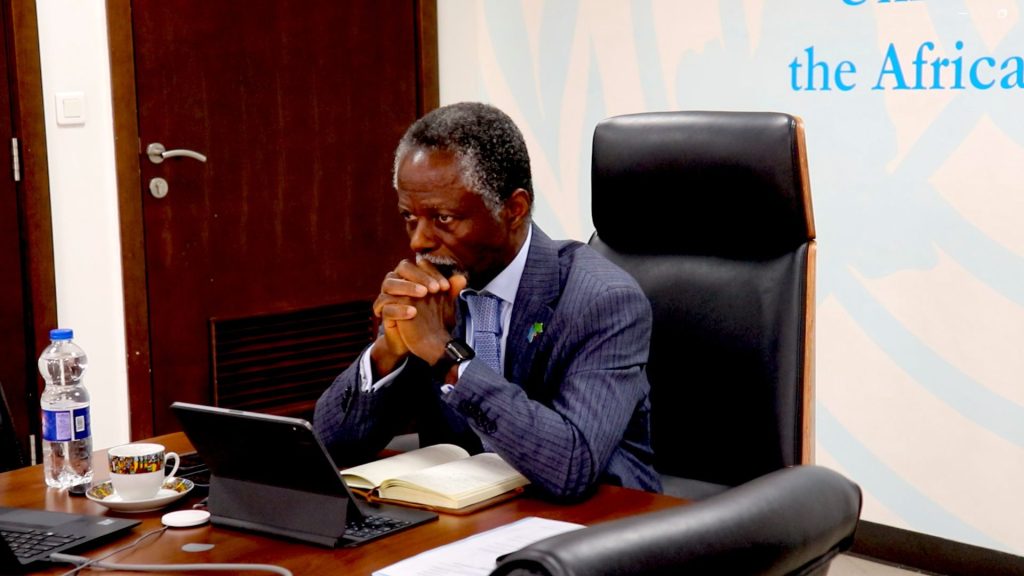

On 19 February 2025, the (then) leader of the African Group Of Negotiators (AGN), and Special Climate Envoy of the President of Kenya, Ali Mohamed led high-level discussions in Moscow with Russia’s Presidential Representative on Climate Issues, Ruslan Edelgeriyev, and Alexander Novak, the country’s Deputy Prime Minister. The talks focused on how both sides could ensure a more equitable approach to climate change, and enhance their mutual positions within international forums. According to a statement, both sides agreed to develop a joint work plan that will include collaboration between African and Russian businesses, technology transfers and a fairer approach to carbon markets.

The talks are no surprise , African countries have long standing economic, diplomatic and security ties with Russia, which have grown in recent years. The war in Ukraine has driven Russian efforts to tilt African sentiment in its favour, prompting concerns that African countries will be stoked into anti-Western sentiment. Western countries have denounced what they perceive to be a destabilising influence by Russia in the continent, pointing to the Russian Wagner Group, a private company operating as a Russian military proxy in many African states, as driving conflict over natural resources, bolstering authoritarian regimes, and undermining human rights.

Last year, Russia was reportedly offering African countries a “regime survival package” with military and security assistance, in exchange for access to natural resources such as timber, gold, uranium and lithium. The proposal followed a tour by Russia’s deputy Defence Minister to Libya, Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Mali and Niger. Speaking to the BBC, land warfare specialist Dr. Jack Watling argued the offer had geopolitical significance: “we are now observing the Russians attempting to strategically displace Western control of access to critical minerals and resources.”

While Russian military involvement in Africa is relatively less than the military presence of China and the West, a long standing frustration with Western intervention, increasing debt levels and dwindling climate finance, resentment over a lack of representation in international institutions, and a desire to not have to repeat cold-war tactics of choosing sides, has continued to prop up diplomatic ties between the regions.

In that context, this month’s meeting between Africa and Russia on climate is not spell-binding. The two sides have already inked numerous cooperation agreements on various issues between them. Official relations have always been modest but growing with Russian influence and aid for civil wars in the DRC, Angola and South Africa stretching back to the cold-war era. However the shared frustration with what is perceived as global inequities perpetrated by the West, is more palpable.

At this month’s talks in Moscow, Mohamed underscored the inequity of many global policies that favour industrialised nations, and restrict Africa’s right to develop using its natural resources. He lamented the pressure placed on the continent to set ambitious mitigation targets, in the context of it only contributing 4% to global emissions and a denial to use a fair share of its resources. “A truly equitable approach should ensure development opportunities for all,” he said.

Mohamed instead proposed that “a fair approach to NDC setting should derive from a fixed global emissions budget divided across all countries based on an equal right for development for all people, i.e. on a per capita basis”, a proposal his Russian counterparts apparently agreed with. According to the International Energy Association, Russia’s global contribution is approximately 4.8% of GHG emissions, but per capita it ranks about 15th in the world.

As a member of BRICS, Russia has long opposed the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) vociferously and both regions are aligned in resisting trade barriers such as the CBAM. “This policy places an unfair burden on African exporters while allowing high-emission countries to maintain their advantage,” Mohamed stated.

Russia’s Char of the Committee on Climate Policy of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, Andrey Melnichenko, underscored the importance of joint action, illustrating Africa’s 1.4 billion people, combined with Russia’s diplomatic and technological resources, could unite as a powerful driver for change to ensure more equitable climate policies.

Both sides also discussed the potential for scientific and technological collaboration in emissions tracking and climate monitoring as a means to enhance their global positions. Mohamed underscored that this was critical to ensure Africa had a stronger voice in global platforms. “Accurate data on emissions and removals will be crucial in shaping Africa’s climate policies and ensuring fair climate finance allocations,” he said. Similarly, Melnichenko, argued that Russia absorbed “twice as much CO2-eq. as previously thought” and is a “much ‘cleaner’ country, and this should be leveraged in international climate negotiations”. Both are looking to science and monitoring data to prove them right.

Russia has long advocated for ongoing fossil fuel use alongside renewable energy, and has opposed calls to do away with fossil fuel investments. African negotiators, while not against a fossil fuel phase out, are desirous of an equitable transition where developed countries bear the primary burden of the phase out, and African countries are afforded more time and support to do so.

Going forward, representatives agreed to develop a joint work plan that will include collaboration between African and Russian businesses, technology transfers, and a fairer approach to carbon markets.

Whether Russia can curry favour with African countries on the diplomatic stage will need to go beyond strategic partnerships. As an Annex I country under the UNFCCC it bears climate finance obligations, however, since the conclusion of the Paris Agreement it has not made any substantial contributions to international climate finance. As global development aid dwindles, Russia will need to do more than a joint work plan. Its alliance with the continent on certain key topics, however, such as the CBAM and technology transfers, may support Africa’s efforts to secure more equitable climate outcomes.

** the press release of the meeting did not emanate from the office of the AGN.