On 20 January 2025, newly inaugurated US President, Donald Trump withdrew America from the Paris Agreement and halted funding to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). His actions have elicited strong reactions from the Global South. In a statement published shortly after the executive order was signed, the African Group of Negotiators (AGN) criticised the decision for being: “a direct threat to global efforts to limit temperature rise and avert the catastrophic impacts of climate change, particularly for the world’s most vulnerable nations. The removal of climate change references from the White House website, the advancement of fossil fuel projects, together with the withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, risk undermining the collective progress achieved under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).”

Whilst there are many dimensions to the withdrawal, one of the key impacts will be on funding. If America is no longer a party to the Paris Agreement, there are fears that climate financing will be further jeopardised, with the US having historically under-pledged and under-delivered. When developing countries created their National Adaptation Plans, it was on the understanding that the UNFCCC’s Green Climate Fund (GCF) would mobilise resources from all developed countries for the operationalisation of these plans. However, the gap created by the withdrawal by the United States, which had historically pledged US$3 billion to the GCF, will see developing countries having to draw on fiscally constrained national budgets.

Furthermore, “the Loss and Damage Fund is likely to be underfunded, thus exposing developing countries to be more vulnerable,” said Zimbabwe’s Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Environment, Climate and Wildlife, Ambassador Tadeous Chifamba in an interview with Environpress Zim.

The statement by the AGN reflected the same line of thought. “For Africa and other developing countries, the implications are severe. Africa, already on the frontline of the climate crisis, faces escalating droughts, floods, and extreme weather events that threaten lives and livelihoods, exacerbate food insecurity, and destabilise economies. The withdrawal of US leadership diminishes the critical financial and technical support required to adapt to these challenges, leaving vulnerable nations to bear an unjust burden.”

Dr Sandra Bhatasara, a researcher who specialises in the sociology and anthropology of climate change, fears developing countries will never get the climate finance they deserve. “I am not very sure how things will play out in the future. But as it is, it means the reduction in climate financing. We are already debating about the Loss and Damage Fund. There is not much in that fund if you look at it. We celebrated when it was created in Egypt (COP27), but we went to Dubai (COP28) and Azerbaijan (COP29), bickering happened because money is just not coming out to be able to support developing countries in adaptation and resilience and all those aspects in terms of loss and damage. So this is a big deal because we are losing those funds.”

Will Africa and the rest of the Global South be unable to unlock domestic climate finance?

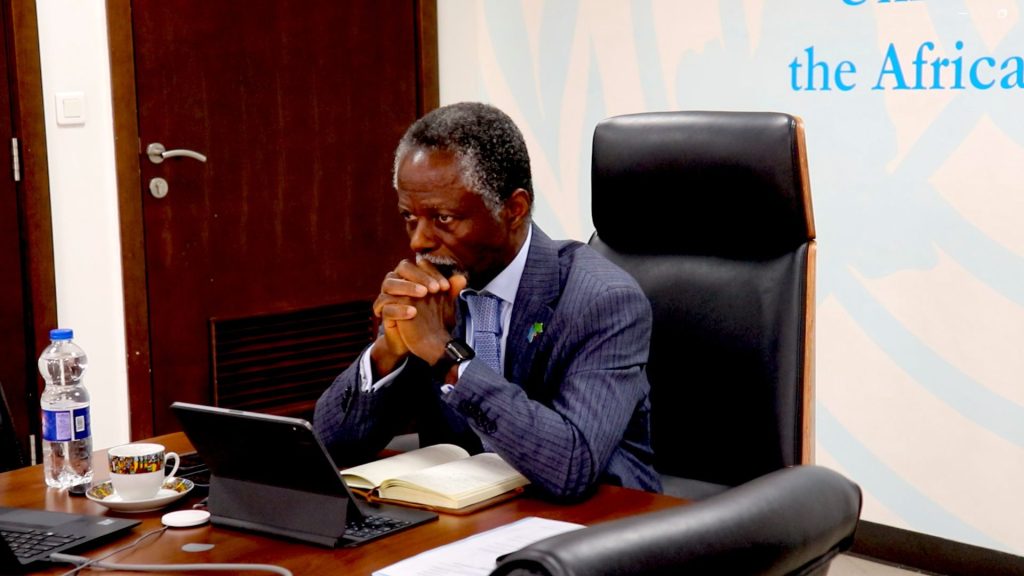

“Based on the outcomes from the 2023 African Climate Summit, it was agreed that Africans must not be seen as beggars but as equals to both climate finance and coming up with solutions. Several initiatives have been taken to support regional projects on both climate change and biodiversity,” said Dr Oldman Koboto, MEA Coordinator for the African Union Commission at COP29.

But Dr Bhatasara has a different view. “I appreciate others who say let’s respect ourselves, let’s not be beggars and let’s do domestic financing of climate change and all that. We simply are not going to get our governments to do that because of deficits and other aspects. I don’t think we are playing unfairly when we say ‘you guys made this world dirty, clean it up’. The global stage when it comes to climate change was messed up, but now it is worse with the withdrawal of America. I do not think we are going to see environmental multilateralism getting stronger”, she said.

Instead, she felt that it would “embolden those who are denying that there is climate change, not only him but other conservative elements that also counter climate change movements. This means even when negotiating at COP for instance, these people are now even going to do it [climate denial] with even more vigour, and they are going to do it with probably his blessing.”