RIYADH, Saudi Arabia: It was a Conference of Parties (COP) of firsts. For the first time, a UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) summit was held in the middle east region, indigenous groups won a platform at the talks after a decade of knocking, and about $12 billion was raised within the first week of negotiations.

For the first time, the largest, (about 20,000) and most diverse number of participants attended the sixteenth desertification COP (COP16), with an eight-year-old as the youngest delegate. The green zone, which the summit hosted for the first time attracted 35,000 delegates. It was the first of the Rio Convention summits without political showdowns, according to Marcos Athias Neto, the assistant secretary-general, bureau for policy and programme support at UN Development Programme, (UNDP).

“This COP is yours. This subject is yours. The issue of land, water, and how it interacts with people’s lives, and how it is connected to migration, peace, food security, and human health is absolutely critical,” said UNCCD executive secretary, Ibrahim Thiaw.

Yet, its branding as a desertification COP, and the perception that it is the smaller of the three Rio Conventions, had two thirds of the world’s countries thinking it was not for them. This is despite the fact that land degradation impacts during the last three decades have become more visible. This also made it a calmer affair. “This COP is so nice and relaxed. The politics and the geopolitical elements of climate have not yet arrived on this COP, and that is good. It is also a re-invention because it is being re-branded as a land Convention,” said Neto.

But it failed to deliver on what African countries were seeking – an issue that proved to be the most contentious over the two weeks of negotiations: a legally binding protocol on drought under the UNCCD. During the early stages of the negotiations, there was high optimism that a decision for the adoption of a drought protocol would be reached, with Thiaw later describing the mood in Riyadh as positive.

By close of business on Friday, which was the date the UNCCD secretariat set for the talks’ conclusion, the 195 parties plus the European Union (EU), could not agree on a drought protocol deal, spilling negotiations into early Saturday morning. Despite the host country’s best efforts to steer the negotiations towards a legally binding instrument, negotiations were suspended four times due to disagreements.

“I am still hopeful they (negotiators) will have a bold decision that will be transformative, that will provide clear guidance to governments because they have to translate that global decision into national decisions. Hopefully by tomorrow you will see the smoke, and white smoke I hope,” Thiaw told the media a day before the summit’s official closing. However, in the early hours of Saturday morning, parties could not agree on whether to adopt a new drought framework or a legally-binding protocol, and ultimately only agreed to a procedural decision to re-visit talks in 2026 at the COP17 summit in Mongolia.

The Africa group convened in Riyadh armed with draft decisions to convince parties that management of desertification, drought and land degradation across the world must be legally bound by a drought protocol. While drought features briefly in the convention, it was never prioritised historically. The process to adopt a protocol, decision, target or other instrument sought to overcome this. It began at COP15 in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, where the global community agreed to establish an Intergovernmental Working Group (WG) to develop policy options for addressing drought across the world. With Kenya, Eswatini and South Africa representing Africa, IWG produced a report after two years, which the UNCCD adopted as a draft decision.

“Among the seven options the COP provided, Africa was fronting for a protocol on drought. We were seriously presenting this as Africans because we are the most affected continent. This is one of the most comprehensive and proactive policy options that is going to effectively and proactively address drought across the world,” said Dr. Charles Lange, representing Kenya as the UNCCD focal point.

The Africa group’s view is that a legally binding agreement on drought would unlock financial flows, set clear targets and confirm political commitments by the global community to battle drought and save communities suffering from the effects of land degradation and desertification across the world. While Parties to the Convention would be bound to work together, the protocol would also outline institutional arrangements aimed at driving the drought agenda across the world. It would set a course for the private sector to do their part in the estimated $2.3 trillion investments needed by 2030 to restore more than a billion hectares of land, and build drought resilience.

The Africa group profiled the summit as a legacy COP, meaning there was high optimism that it would arrive at transformative decisions in terms of implementing programs on land degradation, desertification and drought shocks within communities. “The mood was that it would be a COP of legacy that would not be a business-as-usual affair and that there would be decisions that would move the agenda before us effectively,” said Lange.

Questions over the negotiations began troubling delegates barely a week into the summit. Civil society groups complained they were only being given space during the plenary to deliver their statements but not during the contact group meetings.

That raised concerns on how sensitive items like the drought protocol were being negotiated, given that some delegations like those representing the United States and Japan were opposed to a legally binding agreement on drought. It is unclear why they opposed the protocol, but they also claimed to be at the summit as observers only.

The EU insisted it would support the adoption of a drought protocol if climate change was incorporated into the document, an issue that was vehemently opposed by the African group. This was fueled by concerns that including it would divert financial flows from the real issue, namely finance for drought management.

“The most important thing in the negotiations is not to deliver statements on the floor, but member states must be more transparent and open contact group negotiations to allow observers to be in the room to ensure negotiations are going well,” said Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, the president, association of indigenous women and peoples of Chad.

The science is clear on why the world needs a drought protocol. Three quarters of land on earth became permanently dry in the last three decades leading up to 2020, compared to the previous 30-year period, according to the UNCCD. Some 7.6% share of the earth’s lands, or an area larger than Canada, became arid (a situation that turns productive lands into deserts), stressing agriculture systems, ecosystems and communities’ livelihoods, according to a UNCCD scientific report. Nearly half of Africa’s population, or 620 million of its population live in drylands, with Tanzania and South Sudan leading in dryland expansion. The continent’s GDP declined by 12% due to aridity between 1990 and 2015, with Kenya projected to lose 50% of its maize yields by 2050 due to high greenhouse gas emissions, says the report.

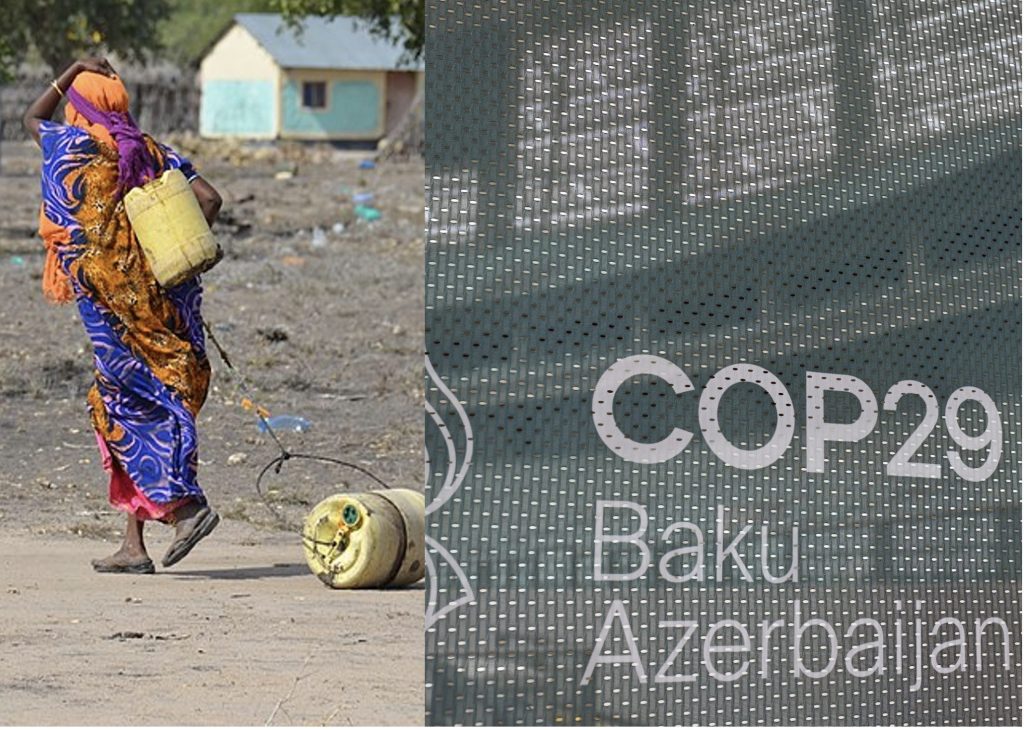

Drought is afflicting social, economic and political systems, especially among marginalized African communities. Stress due to worsening drought and water scarcity is flaring conflict, forced migration and loss of human dignity.

“Coming from an indigenous community it is so obvious to have a drought protocol. People facing drought and water scarcity are migrating and even fighting each other to kill due to lack of resources,” said Oumarou. “Having a drought protocol can guide governments in a concrete way to take action at the local and national levels and report back to the Convention on how justice can be served to the people who are suffering,” she added.

But why a protocol on drought and not a land, or both, including desertification? According to Osama Faqeeha, the Saudi Arabia deputy minister for environment, the Convention has an instrument to address land degradation and desertification covered under the Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) target. Its goal is to ensure the amount and quality of land resources necessary to support ecosystem services and enhance food security remain stable or improve over time, and aligns with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 15.3. Over 130 countries have committed to setting LDN targets and integrating them into their national development and environmental policies, said Faqeeha. “We already have an umbrella for land degradation. What we lacked was an instrument on drought,” he said.

On the other hand, drought is upending economies, exacerbating disease outbreaks, swinging food prices and drying water sources, as it sends supply chains into a tumult. “There is a growing understanding in the world that drought is affecting our lives like never before, and now affects more than just the rural communities that are totally dependent on land. There is agreement among parties that there is need to do something big and meaningful to turn the tide on a slow disaster which is affecting the world,” said Thiaw.

Just like this year’s other Rio Convention summits, COP16 was another disappointment to Africa. Whether the next desertification COP in Ulaanbaatar in 2026 can mend rifts between the global north and south remains to be seen.