Expectations for COP29 are high. A New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) is high on the agenda, intended to replace the old climate finance target. Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) are also up for discussion, with the clock ticking on the 1.5 °C target of the Paris Agreement.

This year’s COP schedule also includes youth-led climate forums and the Local Communities and Indigenous People’s Platform Annual Youth Round Table. There is a history of youth participation and spotlighting at COP. At COP25 in Madrid world leaders and youth activists signed the Intergovernmental Declaration on Children, Youth and Climate Action. The Declaration commits world leaders to delivering inclusive, child and youth-friendly climate policies and action at national and global levels. COP28 saw a significant increase in youth attendance. YOUNGO, the official children and youth constituency of the UNFCCC published a Global Youth Statement that outlines youth demands from COP29 negotiations. Demands included the scaling of adaptation action, financial support for youth-led initiatives and the inclusion of youth and children in plans to transfer climate technologies such as renewable energy, artificial intelligence and carbon capture. YOUNGO also launched the first ever Youth Stocktake at COP28

But it hasn’t been a smooth road. Youth delegates argue that, at best, the agreements and outcomes of COP summits don’t go far enough to address the unique challenges that young people face as a result of climate change. At worst, they argue that governments and business are prioritising profit and geopolitical dominance over climate change, resilience building and adaptation. A lack of ambition, overly complicated processes and disagreements over the language of texts (such as the Global Goal on Adaptation) have stalled progress on transitioning away from fossil fuels, mobilising resources for the Loss and Damage Fund, and finally reaching an agreement on a new climate finance goal. Furthermore, documents such as the Declaration on Children, Youth and Climate Action are not legally binding. Its signatories have no obligation to fulfill its commitments. In the same vein, delegates at COP29 are also under no obligation to heed the demands outlined in documents such as the Global Youth Statement. And while the youth-led climate forums and roundtable discussions can be a way for youth delegates to connect, coordinate efforts and consolidate their positions, these delegates are not included in the high-level negotiations that determine COP29’s outcomes.

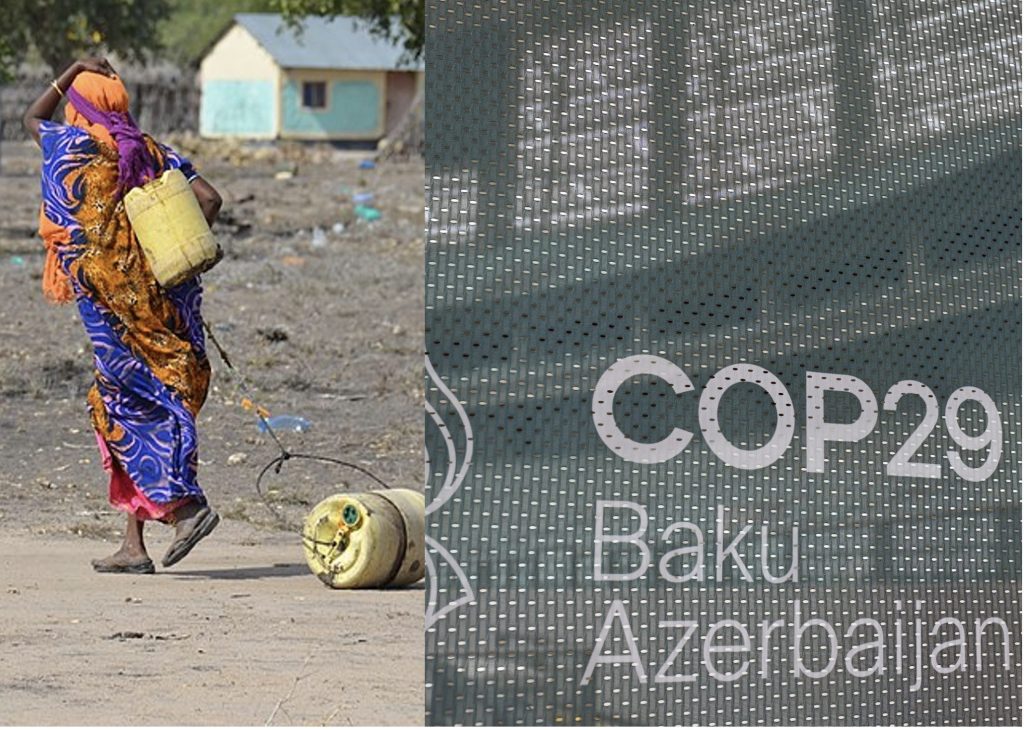

Africa has the world’s youngest population – a population that will continue to increase in the coming years. These youth face a stark future: almost every child alive lives through at least one climate shock a year, with over climate-related extreme weather events leading to the displacement of at least 43 million children since 2017. Panashe Musarurwa is the Ambassador Coordinator for the African Climate Alliance, overseeing a mentorship programme of 30 young Africans to champion climate policies and action in their home countries. For the Alliance, the value of youth participation in climate summits lies in their ability to raise awareness: “they’re the ones that are directly facing the consequences of neglect, regarding the climate crisis and are able to inform world leaders about the needs of the vulnerable communities.” With the New Collective Quantified Goal a key priority for the upcoming COP, enforcing commitments to replenish climate funds and making provisions for funding youth-led initiatives are some of the practical ways that negotiators can signal that they take youth concerns seriously beyond signing pledges.

For Musarurwa, the real value of COP is in the aftermath of the summit. When delegates leave Baku and return to their respective countries and organisations, the real work begins: “at the end of the day, [leaders] can say all these things to make them sound good and pretty at COP. But when you come home, it’s about holding that accountability. There’s a need for public participation to ensure that the decisions are inclusive and fair and not just making decisions based on what the governments want.” Musarurwa points to public consultations for Zimbabwe’s Climate Change Management Bill as an example of bridging the gap between high-level negotiations and policy and local contexts and communities. “It can be extremely daunting for youth because when they attend (COP) they may feel excluded from conversations. But I really believe that it’s important for the youth to keep pushing the message that they want climate justice,” says Musarurwa.

Perhaps then the value of the presence of youth at the COP is how they highlight the connection between effective climate change policy and the wellbeing, prosperity and safety for present and future generations. They have effectively wielded this power and their rights in court room class actions around the world. To continue, they need to have a meaningful seat at the COP29 negotiation table.