When countries met for the global climate science body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) 60th session in late January, they were unable to agree on a timeframe for its next report. The IPCC has just come out of its sixth assessment cycle, a five year process culminating in a Synthesis Report that was released in 2023. These reports are used to inform and guide the negotiations under the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement as well as national action. It is now commencing its seventh cycle, commonly referred to as AR7. But at last month’s meeting representatives of 195 member countries could not agree on the timing for its next synthesis report, or its related contributory reports known as Working Group I, II and III Reports.

The current schedule pegs the end of 2029 as the date for finalising the next Synthesis Report. However, a senior official from India’s delegation reported to the Hindustan Times that “many developing countries were concerned that the agenda of the developed countries was to rush the IPCC AR7 for completion in less than five years (four and a half years or less) and therefore compromise on the quality of the reports. Some developed countries also shared these concerns, notably Russia. Many other developed countries were initially for a longer timeline like the developing countries but slowly fell in line with the US which was pushing for an early timeline.”

The United States, Jamaica, Grenada and other small island states are in favour of a “light cycle” option, meaning that there would be fewer outcomes documents and a shorter timeframe to complete them. The US wanted the “light” option so that the IPCC could to be in a position to release a report in time to guide the next Global Stocktake which is scheduled for 2027-2028. The Global Stocktake is a process under the Paris Agreement for countries to assess, progress in achieving its goals and to plot steps to achieve them on a rolling five year basis. The last one was at COP28 in 2023.

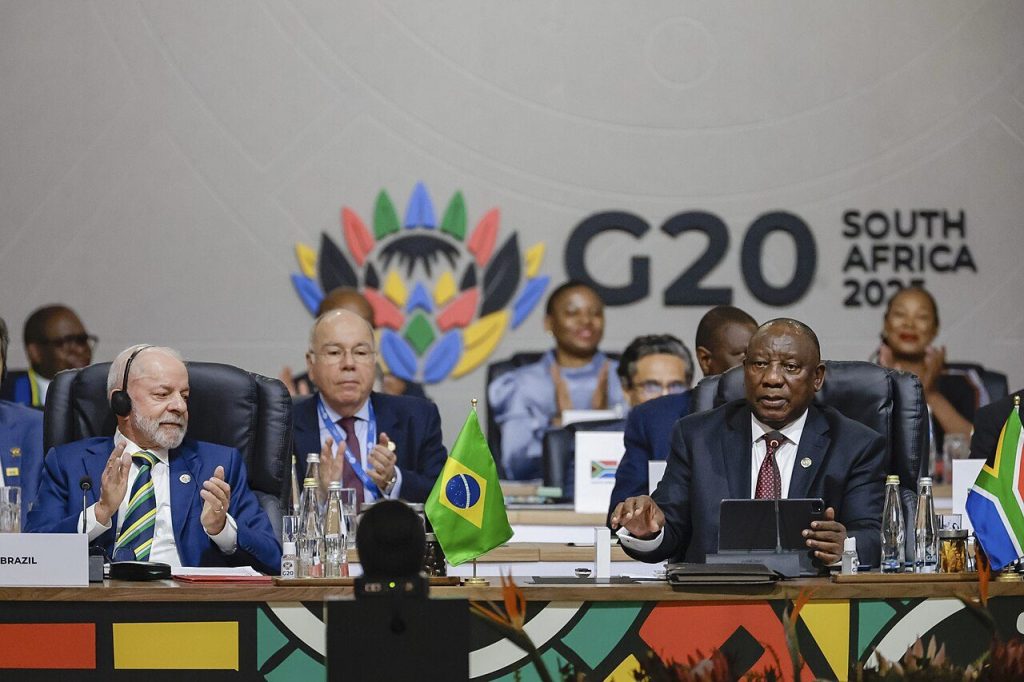

The co-chairs of the IPCC meeting, however, highlighted that accelerating the timeframes would also entail compromises that would likely work against developing countries, a point that India, China, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, South Africa, Brazil, Argentina, Kenya and others were all in support of. The co-chairs pointed out that shortening the time frames may lead to insufficient time to develop literature, shorter review periods for governments, less time for author selection and no chance of additional expert meetings or workshops.

For African countries a shorter timeframe could be particularly compromising. Continental data and literature to build IPCC reports is often lacking, as is capacity. As South Africa pointed out during the meeting, there are only one or two people in developing countries to coordinate the reviews, and limiting timeframes would limit the level and kind of inputs they provide. For this reason, a major priority for African countries in this cycle is to ensure a more balanced representation of scientists from the continent and to address data gaps, but a shortened cycle may hinder this. Some negotiators were also concerned that shortening the timeframe would also enable developed countries to push a specific agenda, whilst developing countries were still in the process of compiling their inputs.

After further deliberations it was agreed that the final synthesis report would be produced in late 2029 (after the second Global Stocktake). There was some desire by developed countries to have the Working Group II report on Mitigation ready by the Global Stocktake to send a “strong signal” on mitigation. It was however agreed that further deliberations would be held on when the interim contributory reports for Working Groups I, II and III would be finalised.

At the session the IPCC also agreed to update its adaptation guidelines and metrics, to create a “distinct product” that would enable countries to better assess adaptation measures. This issue has long been held dear by African countries in the negotiations. Things stalled last year during COP28 discussions on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) and Global Stocktake, partly because there were concerns by developed countries that the percentage target related GGA that African countries were seeking, could not be sufficiently measured. Parties then agreed to defer a decision on metrics and indicators for the GGA. Ultimately a watered down general adaptation goals for health, biodiversity, food and the like, were agreed to for the GGA, coupled with some process related goals. However, having an IPCC updated metrics for adaptation could at least assist developing countries measure adaptation impacts and, in turn, harmonise reporting and potentially also attract greater funding for adaptation measures. At the meeting, a representative from a developing country told Third World Network that “there has been a continuing reluctance among developed countries to focus on adaptation in any concrete form. While it is paid lip service to, they did not want any concrete product focused on adaptation guidelines, metrics, and indicators. Having brought the world to 1.1°C warming due to their inaction on mitigation, it would not have been good to send a message to the world that the IPCC does not want a focused product on adaptation because it has other things on its mind.”

Lastly, while the adaptation update will be welcomed, unfortunately countries did not agree to a special IPCC report on loss and damage. This was mooted in the negotiations last year as developing countries bemoaned the lack of data available to them, which in turn hinders their ability to adequately assess losses and damages, and, in turn claim for them. This was particularly an issue for African countries when compiling the Africa Report for the IPCC’s sixth cycle, as there was limited data on loss and damage for them to include, resulting in the report only having limited case studies. Having an IPCC endorsed approach or methodology to loss and damage would help harmonise approaches and fill data and information gaps. Venezuela, Pakistan and Grenada sought to champion the creation of such a report, however no consensus was reached and countries could only agree to develop a new special report on Climate Change and Cities.