On 29 March, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted a resolution requesting an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the obligations of States with respect to climate change. The initiative was spearheaded by the Republic of Vanuatu, and is the brainchild of a group of law students at the University of South Pacific. Vanuatu has been lobbying for support for its draft resolution for a few months, and in March it announced that it had the support of 105 co-sponsor states.

This marks the formal beginning of the ICJ weighing in on the implications of climate change, being the only major United Nations organ to not yet have done so. ICJ opinions are not legally binding, but they are instruments of preventative diplomacy, and are highly precedential in other legal proceedings. More broadly, according to Nilufer Oral, a director at the Centre for International Law at the University of Singapore, the opinion will encourage states “to actually go back and look at what they haven’t been doing and what they need to do” to address the climate emergency.

Whilst the ICJ has not been directly asked to express an opinion on which states are liable for “losses and damages” associated with climate change, it has been asked to give substantive content to the legal obligations that could be used to establish liability in any future loss and damage legal proceedings. Specifically one of the questions the court has been asked to answer is what are the international legal obligations of States to ensure the protection of the climate system from GHG emissions, and the “legal consequences” of failing to meet these obligations. In other words, could reparations or financial support be a legal consequence. Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s climate change minister has mentioned that the opinion could possibly be used to push for stronger legal measures such as a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty, or the criminalisation of “climate destroying activities” or the crime of “ecocide”.

Law is a slow animal. The resolution needs to be formally adopted at the UNGA which could take a month, and then the ICJ still needs to accept the request (it most likely will). As we have previously reported, the ICJ then has the right to call for written or oral proceedings, which could take several months, with a further period to deliberate. It is anticipated that an ICJ opinion will only be issued in the second half of 2024 or in the first half of 2025. That timing may be prescient as it will inform deliberations on not only the implementation and financing of the loss and damage fund, but will also likely guide negotiations on the new collective quantified goal on climate finance and the next round of NDCs under the Paris Agreement.

The timing of the ICJ process kicking off aligns with the first meeting of the Transitional Committee tasked with operationalising the funding arrangements for loss and damage (including a new loss and damage fund) at COP27, met for the first time in March this year. The two are related in the sense that, should funding arrangements be inadequate under the Paris Agreement, vulnerable states may look to the ICJ to set precedent so that they can seek relief in domestic and international courts and tribunals.

The Transitional Committee’s work is to carry out the mandate given to it at COP27. At that COP, while in principle agreement was reached on the establishment of a dedicated fund, the details around who would contribute and who would benefit (which countries are considered “particularly vulnerable”) were left open. A particular sticking point will be whether emerging economies like China will be required to contribute, something that the EU was adamant about last year. The job of the Transitional Committee is to make recommendations on the fund and funding arrangements for loss and damage for consideration and adoption at COP28 at the end of this year. These recommendations cover a wide remit, and include not only recommendations on the institutional arrangements, modalities, structure, governance and terms of reference for the dedicated fund, but also include recommendations on the broader finance landscape for loss and damage and how to operationalise “new funding arrangements” that mobilise new and additional finance, expand sources of funding, and coordination with existing funding arrangements (such as regional insurance schemes). For example, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’s has long called for a windfall profit tax on fossil fuel companies to raise funding, whilst other developed countries are eying the IMF and World Bank as sources of new funding. Either way, the Transitional Committee’s task is a fraught and complex one and it will be difficult to execute in time.

During its first meeting in March in Luxor, Egypt, it elected Richard Sherman (South Africa) and Outi Honkatukia (Finland) as its Co-Chairs. To support its work, a technical support unit has been established, consisting of staff seconded from UN agencies, international financial institutions, multilateral development banks, and the operating entities of the Green Climate Fund. The talks did not focus on substantive issues as the main agenda item was agreement on the workplan. However, during the meeting, members debated the current gaps in the financial architecture and how the new funding arrangements and the fund can help bridge these gaps. Participants were divided on whether to focus on identifying gaps, before working on the fund’s mechanics or to do both simultaneously. Either way, delivering on both mandates will be tricky, given the tight timeframes. Mohamed Nasr, Egypt’s lead climate negotiator, responded that country’s had different interpretations on what was agreed to last year, and what should be prioritised. Unsurprisingly developing countries are prioritising the establishment of a fund, whilst developed countries are more focused on alternative funding arrangements. There were also debates of which countries stand to benefit. The G77 plus China want the whole group to benefit, whilst developed countries want a narrower group to be identified.

What was not discussed was which countries will need to pay into the fund. Despite broad agreement that rich countries responsible for the most emissions should pay, there was no agreement on whether countries such as China should also contribute. China has historically emitted 11 percent of global emissions, second only to the United States. At COP27, several developing countries rallied around its claim that it should be a recipient and not a donor, based on the underlying principle of common but differentiated responsibilities under the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement. The US will be loath to contribute to a fund that China can draw from.

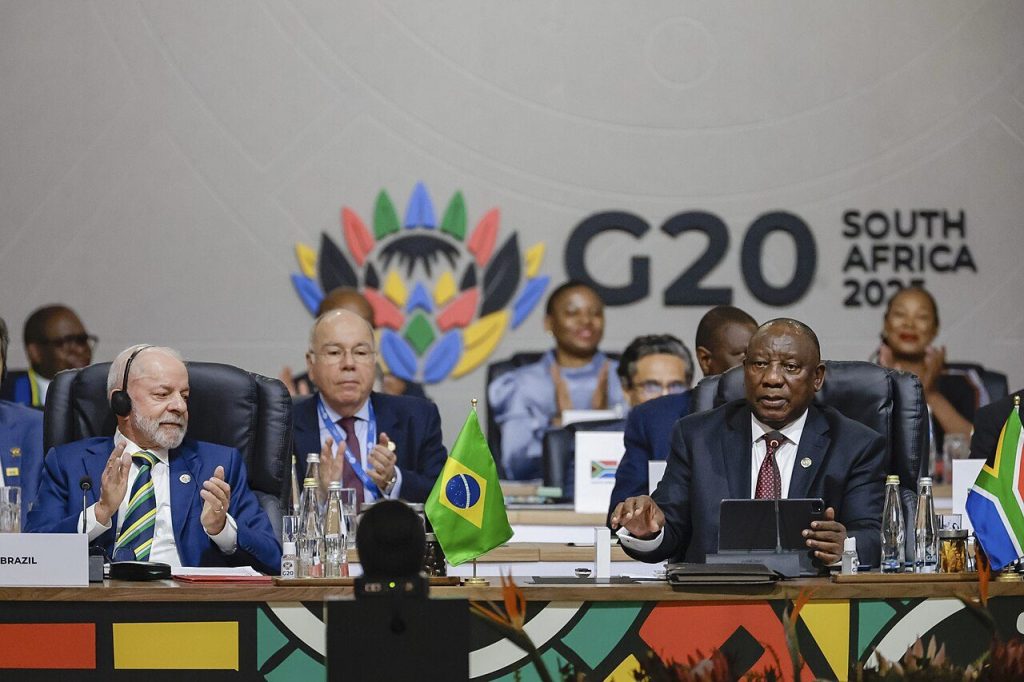

But attributing liability isn’t an easy question. By comparison, in legal damages cases, it is often a matter of debate between technical experts, adjudicated on by a judge, on which party can provide the better evidence to apportion liability. We would anticipate apportioning responsibility between States (i.e. identifying which ones have to contribute to the fund) to be an equally fraught process, if not more so. If these were legal proceedings there would be different ways of arguing for apportionment, based either on historical emissions on a quantitative or per capita basis, or on a temperature basis depending on the climate model used. There is an increasing body of academic literature that opines on the apportionment of responsibility and, ultimately, liability which also comes into play. For example, in March, an article in the journal Scientific Data, sought to assign responsibility – in the form of temperature increases – to individual countries and country groupings, rather than just emissions. According to the article, the US alone is responsible for the largest share of global climate change, having caused 0.28C of warming between 1851-2021, or 17.3% of the globe’s temperature increase. Analysis is also done by negotiation groups, thus, the BRICS Group (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China) jointly contributed to 0.37C of warming during that period. On the other hand, so-called Annex I (developed) countries, are responsible for pushing global average surface temperatures upward by 0.72C since 1851. There are also other factors that might come into play, such as acts by the State claiming the loss that contributed to the harm; the level of knowledge and awareness at the time the harm was caused and when a line could be “drawn in the sand” for liability. Whilst these are not legal proceedings, these certainly might be some factors that the Transitional Committee may be forced to consider. We suspect that ultimately it will be a negotiated outcome of who will contribute, based on a myriad of political and financial factors, however, the legal and equity grounds will no doubt inform these discussions.