States are increasingly using climate change as a justification for imposing new trade measures. While their potential positive impacts on the climate are yet to be determined, many are questioning whether these measures are legitimate and will achieve stated objectives, designed equitably, and whether they contravene global anti-protectionist trade rules.

Earlier this month, Bloomberg reported that both the US and EU were considering the imposition of new import tariffs on Chinese steel and aluminium on climate grounds. The notion is still being conceptualised within the Biden administration, but could potentially entail an agreement between the US and EU that sets out thresholds for the application of steel tariffs. It would build on an announcement last year between the US and EU to negotiate a “carbon based sectoral arrangement on steel and aluminium trade”. Last year’s announcement states that the measures are necessary to counter the “flood of cheap steel” by other countries, including China, but it is also intended to “address the climate crisis while protecting [US and EU] workers and industry”. It touts that “[n]ever have two global partners aligned their trade policies to confront the threats of climate change and global market distortions, ensuring that trade works to solve the challenges of the 21st century,” however it also makes much of the domestic jobs that these measures will save, and that it will provide American industries with an “advantage”. Although largely directed at China, it will likely extend to other steel exporters. South Africa, Mozambique, Egypt and Nigeria are material exporters of aluminium, and South Africa and Egypt (possibly in future Zimbabwe) are also material steel exporters and thus are likely to be impacted by any additional steel tariff by the two importers.

In the same week, on 6 December 2022, the EU Council and Parliament agreed to pass new legislation that guaranteed that products sold in the EU are not linked to the destruction or degradation of forests. It will entail that only products that have been produced on land that has not been subject to deforestation or forest degradation after 31 December 2020 are allowed within the EU’s market or to be exported. The new law will require companies to issue a due diligence statement in order to sell products like beef, coffee, and wood within the EU market. Those linked to deforestation will be banned from import and export into the EU. The measures have been justified on the basis that the expansion of agricultural land is the largest driver of deforestation, which is in turn aggravating climate change. The impacts of the proposed rule on African exports have not yet been determined and are not included within the proposal. Europe, however, represents Africa’s largest export market. Although, Africa remains a net agricultural importer, the EU represents approximately 25% of African agricultural exports. Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Zambia and Mozambique are also material exporters of timber. Undoubtedly they will also impose a procedural burden on exporting states.

Lastly, this week, the EU Parliament and EU Council finally reached a provisional agreement on the upcoming EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) legislation. The CBAM has been justified on the basis that it will create a level playing field by equalising the price EU companies currently pay for their carbon emissions under the EU’s emissions trading scheme, with those of imported goods. Indirectly it seeks to avoid “carbon leakage” by preventing EU companies from moving their production bases to countries with lower carbon prices. Importers will be required to purchase CBAM certificates to pay the difference between the carbon price paid in the country of production and the price of carbon allowances in the EU ETS. This means it will be necessary for exporting countries to be able to demonstrate the embedded carbon in their products, to enable certification (which in itself will impose a high procedural burden). Indirectly it will penalise exporting countries that don’t have the same carbon price as the EU, and hearkens back to our earlier analysis on the EUs move towards a global carbon club. According to the provisional agreement, the regime will apply from 1 October 2023, but the transition period has still to be agreed. In the initial phase it will apply to iron and steel, cement, aluminium and fertilizers. Its scope has also just been extend to hydrogen and some downstream products. A decision on whether to include organic chemicals and polymers (which will be highly impactful for some African exporters) will likely be made during the transition period.

The European Parliament claims that the CBAM will be in full compliance of WTO Rules, notwithstanding concerns about protectionism. Also claiming WTO Rules, they argue that it will not be possible to give an exemption to Least Developed Countries (LDCs), although this is legally debatable. In October this year, the EU Parliament pushed for all the revenue generated from certificate sales to be used to support Least Developed Country efforts to decarbonise, however the latest EU Council and Parliament announcement makes no mention of the position on the use of revenues.

The likely impact of the CBAM on the wide breadth of African exports is not yet well understood although studies are underway. In a post by the Centre For Global Development earlier this year, the authors point out that Egypt, Mozambique, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and South Africa appear at least once in the list of top 10 importers most affected in each CBAM sector. Egypt and Algeria are big exporters of fertilizer, and Algeria is also the EU’s fifth largest cement exporter. They also point out that 54 percent of Mozambique’s aluminium exports went to the EU in 2019, and the country possibly could stand to lose 1.6% of GDP because of the CBAM. Their view is that “imposing a blanket tax on carbon-intensive industries will most likely affect weaker economies and reduce their profit margins associated with goods from such industries… A tax on these products could mean that the mitigative burden of industrialized nations is shared across developing countries.” They suggest that the EU grant a delay in implementation for African countries given the unlikeliness of carbon leakage to Africa, and that CBAM proceeds should be used to foster low carbon growth in LDCs. The merits of the latter approach and the overall philosophy of the CBAM and what it seeks to achieve are debatable, but it certainly warrants further discussion before unilateral measures are imposed.

Trade offers an interesting and important avenue to pursue a climate agenda, and potentially it could be effective if measures are fairly and meaningfully designed to address the true drivers of climate change and not guised as protectionism, take into account the needs of developing countries, do not impose unfair procedural burdens and associated costs on exporting states, follow a meaningful engagement process where developing country inputs are taken into account in the design, and where revenues and financial benefits are not used in a way that provides an unfair benefit to importing states at the expense of developing countries. However, little consultation or engagement has preceded these planned measures, and the initial designs suggest that they predominately stand to benefit the EU and US. The pace and breadth of the proposed trade measures, as well as the design flux they have undergone prior to implementation, have left many wondering what the impact will be on African exporters, with few quantitative assessments currently available. This makes it even more challenging for African countries to meaningfully object or propose reforms to the trade measures.

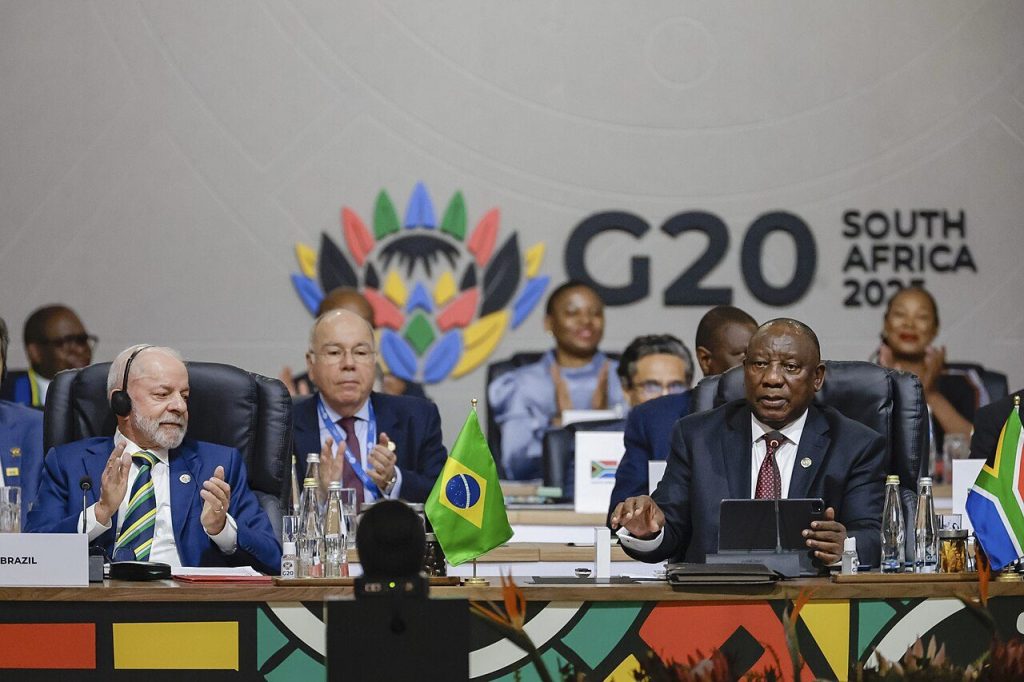

In this context, it is understandable that at COP27 this year, Brazil, South Africa, India and China, critiqued the use of “unilateral measures and discriminatory practices, such as carbon border taxes, that could result in market distortion and aggravate the trust deficit amongst Parties”. They also called upon developing countries to launch a united response to an unfair burden shifting of responsibility from developed to developing countries.