The Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) was established under the Paris Agreement, as a political compromise to elevate adaptation to that of mitigation. In the lead up to negotiations in 2015, the African Group of Negotiators (AGN), had envisaged that it would operate as an adaptation equivalent to the global temperature goal of limiting rises to between 1.5°C and 2°C. In the Paris Agreement it was ultimately agreed to as both a qualitative and quantitative goal, but it has yet to be formally established.

Agreement on the content of the GGA and methodologies for its measurement is important, not only because it provides a system for tracking and assessing countries’ progress on adaptation actions, but also because it can be catalytic for adaptation finance. It will strongly influence what type of adaptation actions might be prioritised and what the international community will count as meaningful.

Like many political compromises, the language used in the framing text of the Paris Agreement is broad and open to interpretation. It has been criticised by the IIED for leaving many questions unanswered, with methodological issues tangled with political agendas and respective capacities of countries. Some of these issues include how to define the goal given that adaptation differs across countries, contexts and populations, but also how to communicate and report on adaptation and how to assess progress on achieving the GGA. Adaptation practice is deeply complex and it can be challenging to aggregate nationally and globally. As the WRI have also pointed out, there is “the need to embrace the diversity of local and national experiences, without adding a reporting burden to countries who already face a myriad of reporting requirements”.

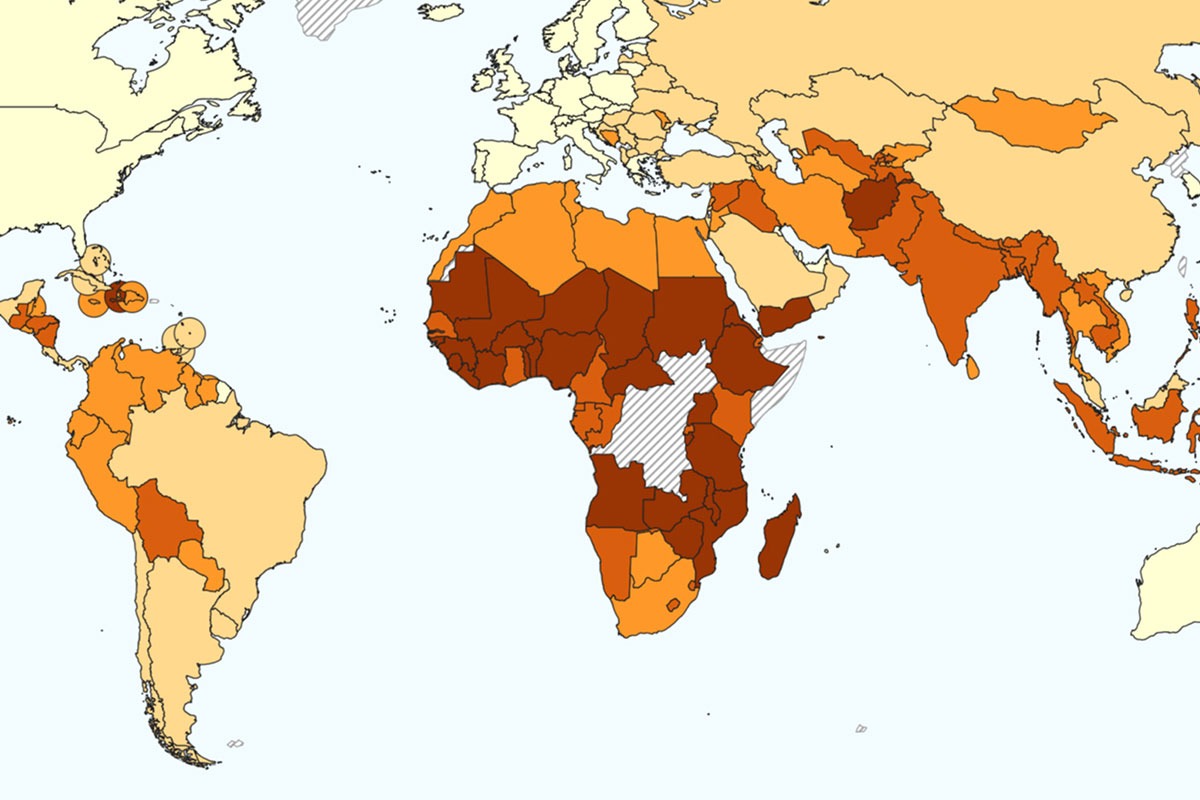

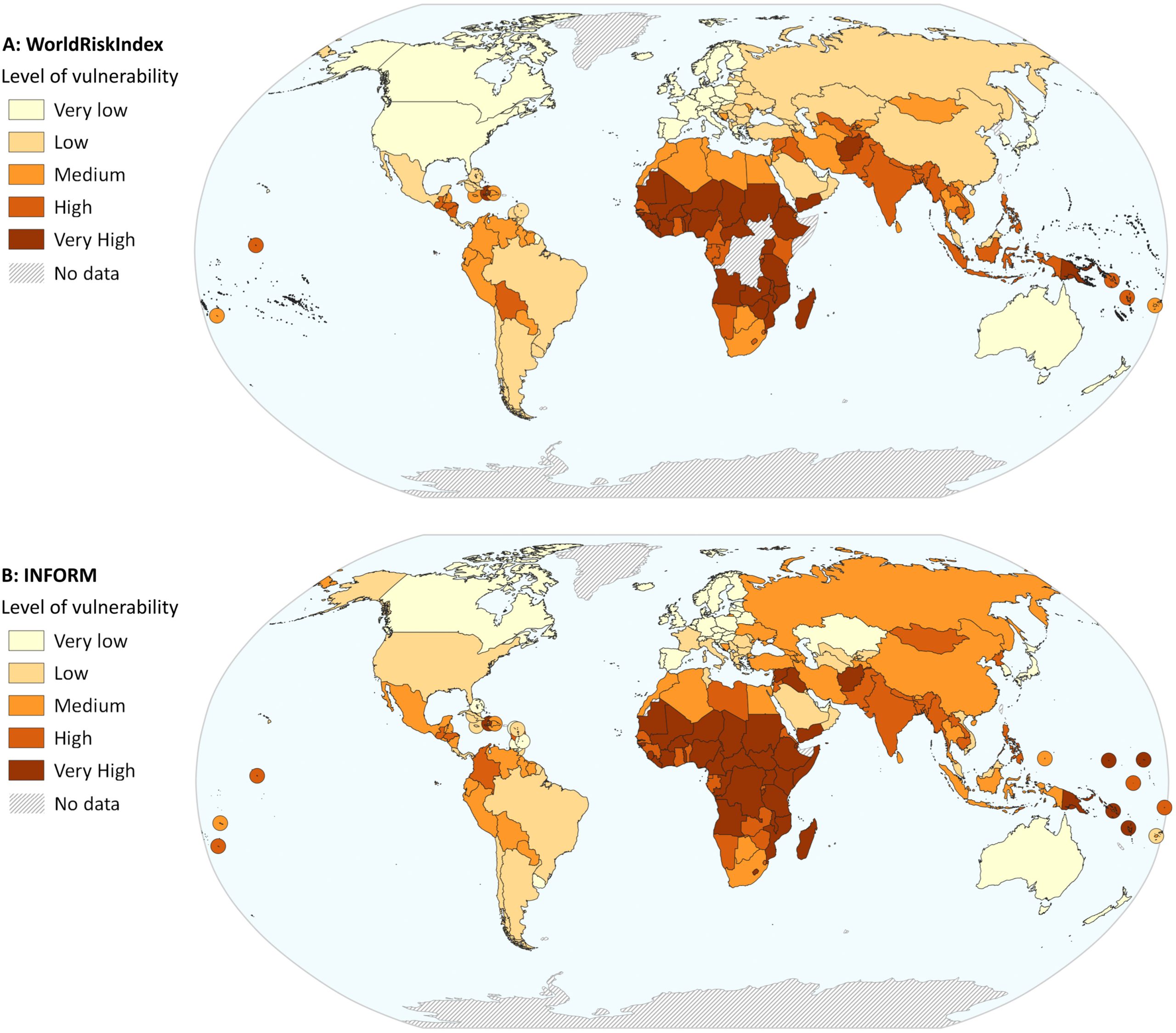

Global vulnerability maps based on the WorldRiskIndex and the INFORM index. Birkmann et al “Understanding human vulnerability to climate change: A global perspective on index validation for adaptation planning” 803 Science of The Total Environment (2022)

There is currently no clear definition on what must be measured, and at which scale progress will be assessed — for example based on national goals or sectoral plans. From a developing country perspective, there are concerns around the resources and capacity needed to collect large volumes of adaptation data when following robust methodological frameworks. This in turn can lead to differences in data quality and a negative bias in the data, creating the impression that little has been achieved.

After the Paris Agreement there was a hiatus in addressing the GGA, however pressure has mounted now that the first progress review is due in 2023 as part of the Global Stocktake. At COP26, Parties agreed to the two-year Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work programme on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GlaSS) to further work on the GGA. Most recently, a synthesis paper has been released by the secretariat, that seeks to compile information and explore ideas and examples of indicators, approaches, targets and metrics relevant to the GGA, with a view to putting options on the table of what a GGA might look like.

The Report engages with the outcomes of the first workshop under the GlaSS, documenting some of the high-level principles/conclusions that were agreed on. These included an agreement that whilst the GGA was global in reach, it could have several targets at different scales (e.g., global, regional, national and local) and use a layered approach with different thresholds of action and ambition.

It also engaged with how other target setting frameworks such as the SDG indicator framework and the Sendai Framework could be built on to develop a GGA. In doing so it explores what these various indicator frameworks are and how a GGA could possibly build on them. It also canvasses studies that give examples of how adaptation progress might be monitored and gives case studies of various information management systems and assessment methodologies.

The report ends in a discussion on the different approaches that could be used to setting a goal, highlighting differences between the timeframe under consideration and overall theoretical approach. It concludes by touching on the possibility of expanding existing goals such as those for disaster risk reduction (Sendai Framework); development (the SDGs); and biodiversity (Convention on Biodiversity), to include other sectors such as coastal resources, human health, agriculture and water resources. What this suggests is an intention to build upon what is already in place for sector specific goals, and to expand it to other areas and, potentially, cascade this down from global to national levels. The report creates an impression that while we are still far away from reaching agreement on a GGA, there is a degree of consensus on the guiding principles emerging from the first workshop and that there are at least potential options on the table that are being discussed with increasing granularity.